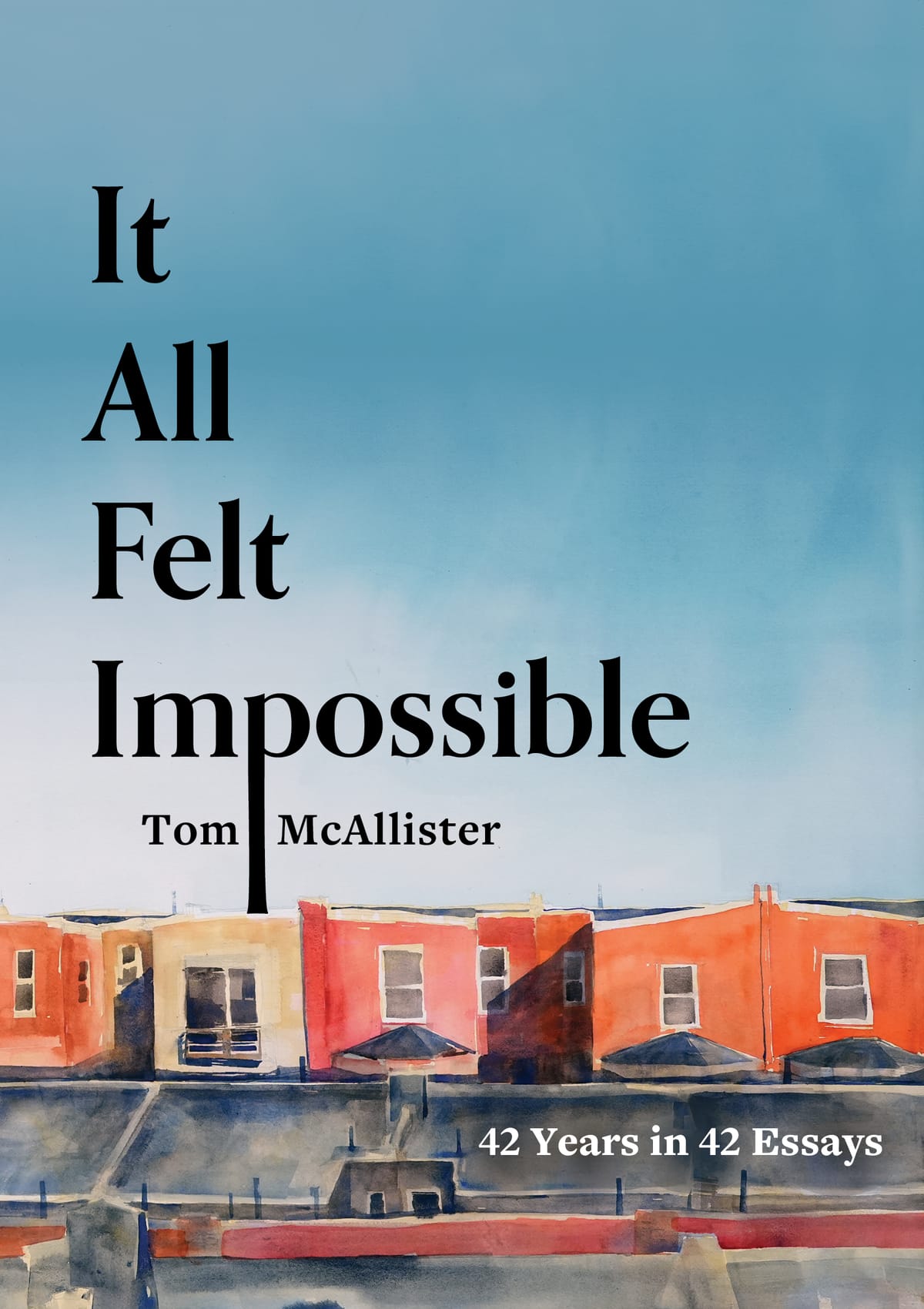

It All Felt Impossible

A quick break in the action. My friend, the author Tom McAllister, has a book out, and it is, in my opinion, good. So I interviewed him about it.

I was friends with Tom McAllister before he knew me. He was one of those regular voices, which you'll understand if you ever listened to podcasts. That's something I used to do more than I do now, but back in the day I used to consume them by the bushel or however podcasts are gathered. Tom was the co-host of Book Fight, a podcast about books that features pretty much no fighting, just Tom and his fellow Iowa Writers Workshop grad and Temple professor Mike talkin' books in an easygoing kind of style that makes you want to listen.

Came the day I became an author myself, and Tom and I got to know one another on the internet, mostly on Twitter (remember Twitter?). He gave me my favorite blurb for my novel The Revisionaries, in which he said that it was as if Kilgore Trout had been commissioned to write the Old Testament. My publisher asked him to change Kilgore Trout to Kurt Vonnegut, and Kurt probably does have more name recognition than Trout, but still I thought it was dumb to change it, and probably Tom did too, but he gave the OK and wasn't that nice of him?

And then one day I guested on Book Fight, where we did not fight one bit, but we did discuss In the Skin of a Lion by Michael Ondaatje, and it was very strange to hear the familiar voices talking to me in their easygoing style, but a pleasant sort of strange, and I talked back in a less easygoing style, which is my wont, and it was a fun time, and if you wanted to listen to it, literally nothing could stop you.

Book Fight is coming to an end, by the way. All things come to an end, but Book Fight is coming to an end this summer. It was good. I'll miss it. They asked every guest which author from all of history they would fight. I think I said I wanted Hemingway. You gotta punch the big dog.

Anyway, that's not the point. The point is that Tom wrote a book called It All Seemed Impossible, and he asked me if I'd like a copy, and I said hell yeah I want a copy of your book, internet friend Tom, whose spoonerized name is "Mom McTallister," which is one of my favorite spoonerisms.

And then I read it. It's a book of essays, in which Tom writes around 1 to 2 thousand words (that's 3-5 pages) on each of the forty-something years of his life. And it grabbed me.

It's not the sort of thing I write, as you'll see, but it sits in a nearby neighborhood. It's about a guy who is sort of around the same age as me, having many of the same experiences, and coming to many of the same sort of realizations. What I guess I'd say is that if you've been following the journey I've been on, there's a good chance you'll like Tom's less overtly political, more personally-realized version.

I think, I thought to myself, that the readers of The Reframe would like this book.

So I decided to interview Tom for you.

As you say in your intro, this book was born out of a project you created to break through a rare patch of writer's block, with a few specific restrictions but otherwise open-ended. I think one thing that caught me is the degree to which your present-day political awareness retrospectively informs what you find by looking back. You're not a polemicist, and your essays are observational in nature, but to my eye your discovery of hints of the shape of what is to come represents a detectable theme. Was this a surprise to you as you went? Did it shape the project in any way as it continued? What was it like to encounter old memories that had perhaps taken on new shades of meaning?

Well, at least one of us is in luck, because I just boarded a 4.5 hour train to Providence and have all the time in the world.

I've been thinking about this kind of thing a lot lately, as an occasional memoirist who doesn't live an especially exciting life. You're asked, not unreasonably, to justify why your story is worth reading and thinking about. (As an aside, I do believe strongly that ANY life is worth thinking deeply about, even if I grant the premise of the hypothetical question). One way of thinking about it, then, is to reconsider stories you've told before, stories you've internalized and accepted as basically true. What did 25 year old Tom think about this incident, and how is that in conflict with 43 year old Tom's perspective? That internal tension--what Philip Lopate calls "the intelligent narrator"– is what drives great memoir for me. It's not just a list of incidents, but an author making meaning, defining and redefining themselves in relation to those incidents.

All of which is to say: it's very much in the DNA of the book, but it also caught me off guard, especially in drafting the first 20 essays or so. I explicitly did not want this to be a Donald Trump book, but I started writing it in 2019. I was revising it for publication in 2024. It's impossible not to have my thinking affected by the political realties of the last decade, even when thinking about some of the racist incidents of my youth. In some cases, I had to fight the impulse to feed the polemicist, because I don't think I'm good at that kind of writing, nor do I feel like I'm the voice people need to hear on some topics. So a big part of the challenge was finding that balance between the personal and the external.

I promise I'll keep the future answers shorter. Unless this train gets delayed.

As somebody who writes long, I think you should make the answers even longer. Maybe a few really terse one-word replies to spice things up.

What other tensions would you say your "intelligent narrator" discovered while engaged in this process? Any other big surprises?

One thing I enjoyed in this book was digging into stories where there is no definitive memory and/or I have vivid memories of events that I'm certain could not have happened the way I remember them. Teaching nonfiction courses, I often have students raise the question about how to write about parts of their lives that are in a sort of gray area factually; they have competing versions of the event with others who were there, they now realize the story they'd believed for so long is a lie, the person who could confirm the facts has died, etc. It's an understandable concern; nobody (well, almost nobody) wants to deliberately lie in a memoir. But I think it's a mistake to shy away from that uncertainty; because whether you're right or not, you remember this thing happening. As Tobias Wolff says at the opening of This Boy's Life, "Memory has its own story to tell." Which is a long way of saying, in response to your first question, I had a lot of fun writing those first 12 years or so, when either my memories are foggy or I have no chance of knowing what was going on, and trying to use some essential facts and my current knowledge of self and family dynamics to tell a meaningful story. Those little fragments are entry points, and as long as you're honest with the reader when you're speculating, I think it becomes a really interesting project to interrogate the formation of one's own memories, which details have stuck with you, and so on.

Shorter answer: I learned that I spent 30 years of my life robbing myself of opportunities and experiences because of completely unfounded anxieties. Seeing it laid out like that, it's hard not to try to make some changes.

One thing I sense in your writing is not just a sense of an expectation to justify your writing, but a cataloguing of your sense that there is an expectation on you to justify yourself (or maybe your self), and a growing awareness that maybe you don't actually need to do that, that existing is just fine and its own justification. (I'm reminded of the recent movie Perfect Days if you've seen that.) Do you see that movement, either in your approach to your writing specifically or to your life? How do you think about it now?

I haven't seen Perfect Days! Though I've considered seeing it, which maybe counts? But yes, I think you nailed it; this wasn't an arc I had in mind when I started it, but as I got to the final 7 essays or so, I especially felt like the story justifies itself in the details. You write it as well and honestly and engagingly as possible, and you don't try to oversell its importance to the reader. One common thread in my favorite books, regardless of genre or content, is a strong and engaging voice. I want to spend time on the page with an interesting and thoughtful person who is inviting me into their idiosyncratic mind. For better or worse, this book will succeed (or not) based in part on whether people think I'm a good guy to hang out with for a while.

Did you find yourself giving each essay an informal name outside of the title it has in the book, which is a year? (Confession: I did this, and really enjoyed Coldilocks, Reggin Haircuts, C+ Bitch, and Crying A Lot.)

Not originally; it was really easy to organize them in my mind just having the years, and then as I started putting it together into a full manuscript, I liked that it was clean and simple and coherent. I also like the idea of people jumping around to random years if they want; though the book is probably best consumed in order, because there are some recurring characters and some threads than grow over the course of the book, you really could just flip to any random chapter and get what I hope is a satisfying reading experience.

During the period when I wasn't sure if this would ever be published as a full book manuscript, I was submitting these individual pieces all over the place, and I considered titling them then. I assume a lit mag wouldn't be especially interested in something called "1988" but, with one exception, they were all cool with it. I think it helped to contextualize what the project was for them right away (so, while Coldilocks would have been a good title for that chapter, this one alerted the editors to the fact that this is part of a larger whole). The one exception is the final piece that was excerpted: "On Wheels" aka "2023" in The Sun. The Sun's editors correctly said that their readers would not likely understand or care about the year-by-year context, and they wanted something more evocative. What was cool about this is that "On Wheels" was the editor's first suggestion--it's an essay about learning to ride a bike as an adult– and I have had a file on my computer titled "On Wheels" for at least 3 years. That file is a bad, half-finished essay about my history of piloting wheeled vehicles (roller skates, skateboard, cars, bikes), and is really just about how I'm very good at parallel parking. That felt like a perfect chance to finally use that title and maybe put that essay out of its misery.

I will add here that I love that you're titling the essays as you're going. Importantly, I love that you're feeling some central tension in each one, and in those 4 examples, connecting them to physical actions or concrete objects. One of the risks of any flash writing or "lyric essay," is to become so unmoored from the physical that you're just wafting abstractions about and hoping the reader cares about how you make pretty sentences. It was really important to me in the writing to make sure I was focusing on physical sensory details first, and doing all the wafting about later.

Time to ask the question you've asked so many others: If you could fight any writer from all of history, who would you fight?

So many great options here. I'm tempted to say Norman Mailer, because come on, but I think he might actually be good enough at boxing that he'd beat me to a pulp. So I'm going to go with my gut instinct, which is Joseph Conrad. I haven't tried to read Heart of Darkness since I was 15, but boy did I hate it then. A teacher then gave me Lord Jim, telling me this would hook me, and I hated that one more! I'm not necessarily going to stand by my 15 year old taste in culture and entertainment (or friends, or food, or.... anything at all), but at that time I despised both books and mentally consigned this author to my enemies list forever. I can't even tell you why I hated them so much, except that for many years after, I refused to read any book focused on a boat, or boat travel, because it immediately brought to mind my distaste for Conrad. (I have since come around on boat books, and there is a pretty decent chance I'd come around on Conrad too, if I gave him a chance, but I feel okay sometimes holding on to the petty gripes of my youth).

Anything else you'd like to tell the people?

My good friend Mike Ingram wrote a great little book a few years ago, and I was immediately jealous of him for having a beautifully made, small book that someone could carry in their pocket and piece through on their commute on the subway (or while waiting at the doctor's office or their kid's softball practice, or whatever). This one isn't quite pocket-sized, but I'm really happy to have otherwise made something that I think feels both ephemeral and meaningful. I've already been hearing from people who are having exactly the experience I'd hoped they would-- "I had 20 minutes to kill and figured I'd read a chapter, and found myself rolling through 6 years." This is, I hope, not just because the chapters are short, but also maybe interesting?

Anyway, that's a long way of saying I'm proud of this book and I think people will like it.

So there you go, cousins. That's my friend Tom; he's not my only friend Tom, but he's the one who wrote a book I think you'll like.

You can find it here if you're interested.

If you're in the DC area or want to travel there, you can see him reading at Kramers in DC on June 18, with Amber Sparks.

That's all. Go back to work. I'll see you this weekend.

Tom McAllister is a writer of many books and stories, the nonfiction editor for Barrelhouse magazine, a professor at Rutgers-Camden, and the co-host of the Book Fight podcast, which is wrapping up its run, and this makes him Marc Maron, basically. You can find him on Bluesky, and also on Instagram and also on his website. He has a mansion and a yacht.

Comments ()