This Is The Last Day Of Our Acquaintance

A little bit about appropriate responses, and a fond farewell to an early teacher.

Yeah, I know, I’m on vacation. But this is on my mind and I’ve got an hour or so. I guess you’re stuck with me.

Sinead O’Connor died last week, and I keep thinking about that.

I never know how the death of a famous person is going to affect me until it happens, but usually the reaction is muted by a certain predictable remove. These aren’t people who know me, and they’re not people I know either; I know of them, and I know their work, and whatever it is they put out there of themselves, and usually that’s exactly how it feels: a sadness to know that someone has gone who without knowing you enriched your life, an appreciation for the gift they had and how it was given, and perhaps a revisitation of that work to enrich the appreciation. But while the person’s death is sad, it doesn’t feel personal, usually. There’s a distance, and in my reaction, I respect that distance as well, by not making the death of a person who didn’t know me into something it isn’t.

That’s an appropriate reaction to such a thing, I think.

It hasn’t been my reaction to hearing that Sinead O’Connor is gone.

This feels like losing someone who was closer than you realized—which again, she wasn’t, so I’m having an inappropriate response, it seems. And it might seem odd that I say inappropriate; you might be thinking dude it’s fine, you’re sad a singer you liked died, that is normal, just own your emotions but I don’t really mean it like that; I’m not embarrassed about the inappropriateness, I’m just recognizing it. I just mean that my brain keeps telling me that this event—the death of a beloved musician—is something relational that it wasn’t. I guess I could say “inaccurate” but it doesn’t feel inaccurate, so I’m going with “inappropriate.”

I keep remembering and then getting a bit emotional about it—nothing histrionic or even outwardly visible but definitely emotional; a sadness that goes deeper, which tells me that the way this stranger touched my life must go a bit more subterranean than the usual, somewhere into the central wiring of me. Sinead O’Connor didn’t know me, but I guess somewhere in the reaches of my brain I decided I knew her, and then I didn’t bother to tell myself that’s what I had decided, until I heard that she was no longer with us, and now I’m telling myself a lot, and that’s not really appropriate to who she was to me, which is a performing artist, or who I was to her, which was nothing at all.

But maybe it’s appropriate to be inappropriate. Sinead O’Connor was often inappropriate; anyway that seemed to be what a lot of people thought of her: an inappropriate woman. An appropriate woman covers Prince songs that go multiplatinum and then accepts awards and accolades politely and then does what her handlers say and makes more hits, and more; she doesn’t sing protest songs and call the Catholic Church an enemy on a live comedy program. After she tore up the picture of the pope on SNL to protest the church’s systemic institutionalized practice of abusing children and protecting their abusers, the next week’s host, Joe Pesci, taped the photo back together to fix the rip in the collective complacency and the crowd clapped approvingly at that, and then he suggested that he’d have physically assaulted her for her effrontery if she’d been there and tried such shenanigans on his watch, and the crowd clapped and cheered to that, too, which meant that unlike Sinead O’Connor they were all appropriate, and so was Joe Pesci, and so was the Catholic Church. So maybe an inappropriate reaction is a way I can pay fitting tribute to an inappropriate women. Fittingly inappropriate, that’s me.

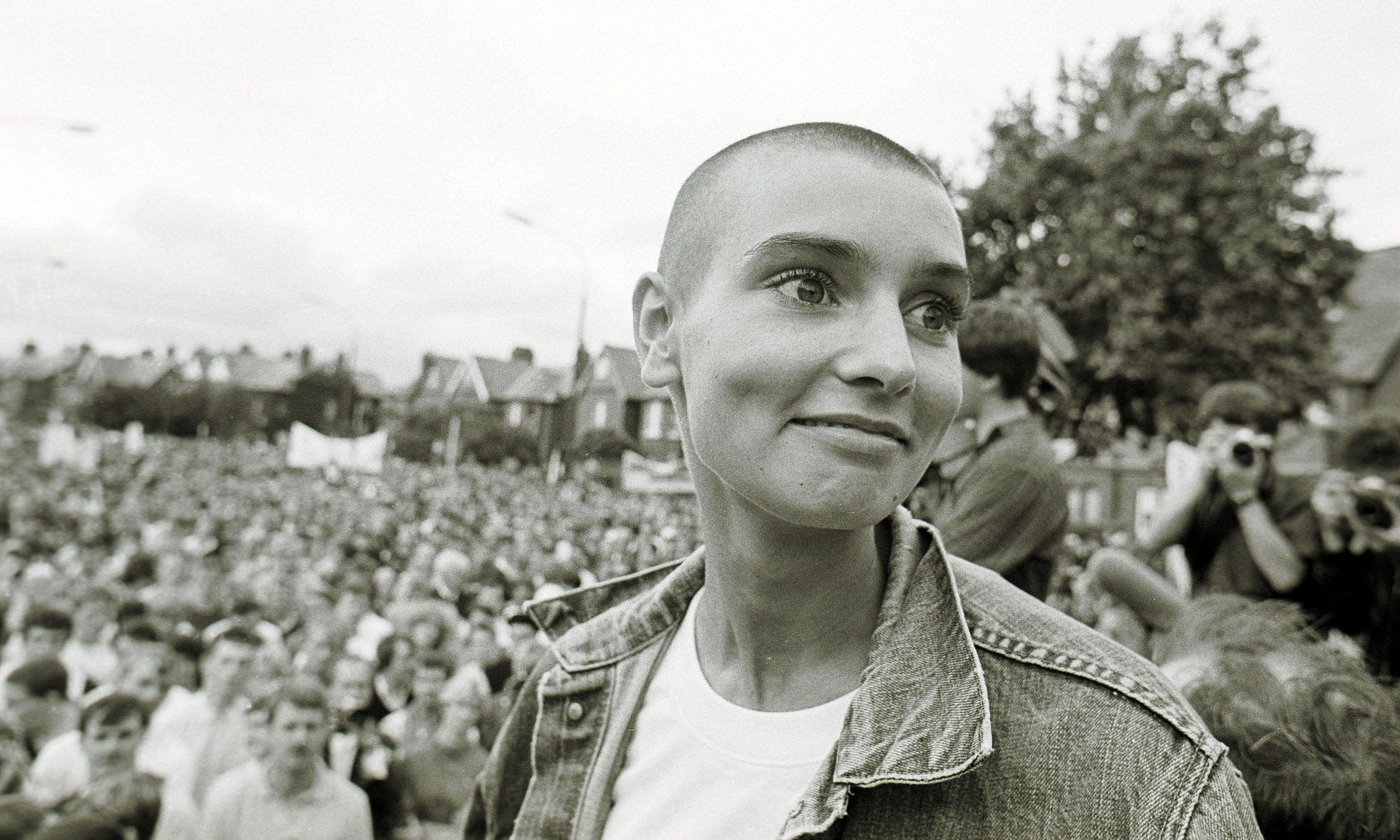

It was my sister that told me the news that she had passed, which I think is also fitting, since my sister, who always listened to the good stuff, is the one who introduced me to her music. And there was a poster of her on my sister’s wall, bald and gorgeous, wearing a leather jacket and ripped jeans with the name of her son, Jake, written on them if I recall.

And if you’re reading this far I think its safe to say you’re familiar with her music, so I don’t have to tell you her way of going from haunted and ethereal to fierce and hungry in a heartbeat, or the way her voice would rise and rise and rise, seeming to carry all the rawness and immediacy of whatever emotions she had brought to the moment, the sadness and hurt and pain and anger and defiance and joy and celebration, too, until your skin would go gooseflesh and your hair would stand on end.

I only saw her perform once, in the late 90s, when she swung by on a leg of the Lilith Fair. Her set was the one I was anticipating most, and she delivered. If memory serves she closed with one of my favorite songs, “The Last Day Of Our Acquaintance,” and her voice did that thing, climbing up to the sky and right down my spine; she was singing about her own lost love, her own regret, her own sweet memories and bitter ones too, yet somehow she was delivering to me—and, I imagined, to all of us—memories of our own experiences of something good come to a close, our own regrets, our own pain.

It occurs to me now that perhaps I experienced her as a sort of impossibly cool older sister, the one who takes you under her wing and teaches you things about the world you haven’t known yet. And I think the thing that Sinead O’Connor was teaching was that the world is a beautiful and wonderful place, full of beautiful and wonderful people, and that the appropriate response to that fact is joy and creativity and love—but also that we humans have bent our societies in inappropriate reaction to this truth, have structured our institutions to press the human spirit into defaults that accommodate greed, cruelty, and abuse, and that the appropriate reaction to such corruption is anger; a creative and artistic anger that is not antithetical to love, but inextricably rooted in love for humanity’s impossible beauty, and scorn for those who would mar it with abuse for their own corrupt gain.

That’s what I believe, anyway.

In my life I’ve sought out teachers who help me understand how to live in this truth.

But it strikes me that the first person who taught me that might have been Sinead O’Connor, who responded to abuse with anger, and was deemed inappropriate for it.

Her lesson wasn’t just to be angry, but why to be angry.

It’s fairly easy to see, now that we’re at a fair remove of time from the event, that our society didn’t feel she was inappropriate because she was angry. In fact, our society believes that anger is a very appropriate response, and will often celebrate anger. Society at large was angry at her, after all—they were furious. Joe Pesci offered to smack her, and the crowd laughed and clapped—just a small part of an outpouring of public validation for the Catholic Church (in particular, also for abusers in general) that abuse could proceed safely and those who spoke against abuse were in danger if they didn’t shut up; public validation that the Church would be able to safely go on protecting the abusers of children for decades to come, and that’s precisely what they did.

No, what our society found inappropriate about O’Connor was not that she was angry, but what she was angry about—that is, corruption and abuse that our society felt was better ignored, angry about the ways that the most powerful human institutions protected not the vulnerable, but the abusers who harmed them.

And it seems to me that O’Connor was rather open about her own messiness, her own pain, the harm that had been done to her. She exposed her wounds and her raw nerves, allowing us to see the ravages of living opposed to abuses in a world arranged to accommodate abusers above any others. So another part of her lesson was to demonstrate that there’s a price to be borne for appropriate responses, a monetary and physical and psychological price for entering into awareness about the ways the world’s institutions accommodate corruption and abuse, a price to caring enough to have appropriate reactions.

And a few years ago, a random playlist delivered her to me again, this time singing “Queen of Denmark,” another cover, this time by John Grant rather than Prince, but once again so perfectly brought to life by her extraordinary gift that it seemed to be waiting for her to come along and finally realize its fullness, and here came that voice again rising with the raw exposed-nerve everything of everything, and my skin went gooseflesh and my hair stood on end, and I nearly wept then because she was still out there, still fierce, still angry, still confident that standing with those who are harmed is preferable to standing with those who do the harming, despite the cost, the damage, the toll.

It strikes me that this was her true offense, the reason she was seen as inappropriate: her anger exposed the reality of institutional abuse, made it so immediate and present that the rest of us would have to stop and think about it. Even if we were only exposed to the truth long enough to furnish ourselves with a reason to not care and then furnish ourselves another reason to not care that we had decided not to care, nevertheless we had been briefly exposed to the natural light of truth, burned by the moral imperative to do something about it, and scorched by our shirked responsibility to shoulder our own part of the burden—and we found that inappropriate, and many of us hated her for that. That was the offense.

In this world, abuse is not inappropriate, and anger is not inappropriate; as long as they are in service to abuse; rather, they are how the world works, and the world will reward abusers for it. No, it is anger about the damage abuse does to other impossibly gorgeous humans, and the demand that it be stopped—that is the inappropriate thing.

As a rather extended aside, I’m reminded that there is a prominent politician who, in the same week O’Connor died, demonstrated in a rather public way that he was in rapidly failing health. I won’t sully her memory by naming him in an essay about her, but he has spent his life making sure that corruption and abuse reign supreme for those who are deemed supreme in our supremacist society, and it’s striking how this conversation has turned the way it inevitably does whenever somebody observably evil is on the way out the door. Now that he appears to be at the end of his life, the conversation is guided, not in an outpouring of memory of what he was, and the damage he has done, the people he has harmed, and the abuses that he has proved extraordinarily effective at assisting and ensuring, but at the inappropriateness of those who would remember these true things about him, the inappropriateness that anyone might celebrate that somebody who has for so long been so ruthless in his pursuit of abuse and corruption may soon and at last no longer be able to pursue harmful ends. It is seen as most inappropriate to notice his lifetime commitment to inhumanity; we are instead scolded to honor the humanity of this man, who never cared for the humanity of others, and in so doing we’re tacitly asked to suppress our knowledge of the humanity of all of his hundreds of millions of victims.

The appropriate reaction to such a man’s life is anger, yet it is deemed inappropriate.

It’s deemed inappropriate anger because such anger confronts those who observe it with a moral duty that each of us carry, to pay our own share of the price of abuse, rather than avoid the cost and force the victims to carry the full burden all by themselves.

That’s what I believe, anyway.

In my life I’ve sought out teachers who help me understand how to live in this truth.

And it strikes me that the first person who taught me that might have been Sinead O’Connor, who once said “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” It’s a quote that’s being attributed to her, though a bit of digging tells me that she herself was quoting Jiddu Krishnamurti, and reading about him makes me think I ought to read even more about him. So it seems even teachers have teachers, which strikes me as a comforting thought.

This morning I’m sitting in appreciation for our teachers, especially our early teachers, and offering a farewell to a great one, who deserved much more than she got, and got much that she never deserved.

She did well for as long as she could, and now she is gone.

She will be remembered. She will be missed.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and is co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He goes out every night and sleeps all day.

Comments ()