Total Eclipses

Make light, reflect light, don't block light. Advice to fellow people of privilege on not being an obstacle. Part 2 of 2.

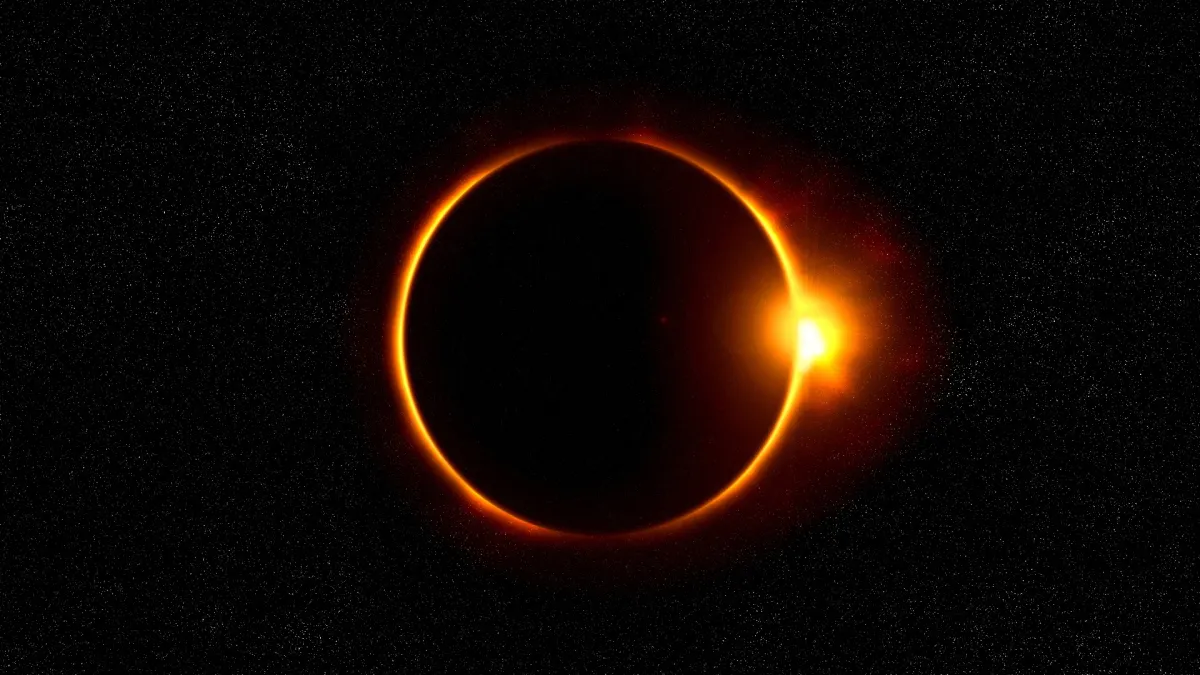

A moon can reflect the sun's light, or a moon can block it completely. Have you noticed?

Perhaps you've also noticed I've been writing about the necessity for light to combat darkness. Maybe you haven't, which is OK, too. It's a metaphor. The light is the abundant and generative expression of humanity and human relationship in all its wonderful diversity. The darkness is the void of white supremacy and fascism that has captured so many humans and created so much evil in the world. I hasten to add that I'm borrowing it, this metaphor. It's not original to me. That's OK, though; very little is original to me. Once in a novel I turned a priest into several pairs of talking sandals. I don't think anyone ever did that before. Where was I?

Ah! This is a message of advice; things I have discovered about light and dark that help me, and might help you, and so here we are. I should hasten to add, this advice is for those who have been advantaged by American traditions of supremacy, not for those who have been targeted by it. A more detailed version of this caveat can be found in last week's post, so let's link to it.

Last week I wrote about the tendency among people of privilege to claim this light all for themselves, in order to frame themselves as the most knowledgeable about the light, and best equipped to determine who should speak of it, and how. They don't shine, they don't reflect; instead they place themselves between the light and others. So there we have moons again.

Also last week, I wrote about some ways to not do that, because when you do that, you're like the tallest dude at a show, standing when everyone else is sitting, blocking everyone's view of the stage. Is it your fault you're tall? No, but it is your fault you're standing without thought to those behind you.

This week I want to write about a different expression of this tendency of the same people (mostly myself mostly) to block the light—not to claim the light, but to claim the darkness.

I have noticed a certain behavior—online mostly, but out in real life too; whenever anyone suggests some improvement be enacted or points out some cause for hope or celebration, or that one thing might actually be better than another, there are people who leap in to deny it, as if to say I am aware of the darkness, much more so than you—so much so, in fact, that I can see darkness that you haven't even guessed at yet; my understanding of darkness is far better than yours, for you are a fool who foolishly believes there is such a thing as light, who foolishly believed there ever was such a thing.

Sometimes, I fear, that person is me.

Let me give a few examples. The president's big bloated terrible bill passed this month, which means the federal department of kidnapping and ethnic cleansing known as ICE just got an additional $45 billion dollars, and they're spending it on even more kidnap squads and even more concentration camps, and probably lots of comfy masks to protect their identities from potential genocide tribunals. This is alarming, and so people will naturally express alarm at it, which strikes me as an appropriate reaction to an ethnic-cleansing force receiving more funding than the militaries of most countries to enact ethnic cleansing. So people are alarmed, and scared, and some might even express a desire to do something about it; a protest, perhaps, or some other demonstration. Writing letters, making calls. Organizing politically. You know the stuff.

And I notice that when somebody says something like America is descending into fascism somebody else will inevitably hasten to respond with something like America has always been fascist. Anyone saying this is horrible will inevitably hear no worse than it always has been.

And I notice that when somebody says something like I'll be joining the protest next Saturday; I hope you'll join me, somebody will inevitably hasten to respond with something like lol a protest to make you feel good is just a distraction from real action; you'll be back to brunch tomorrow, you're only worried now because it's affecting you personally. Anyone saying lets do [something] will inevitably hear [something] is a distraction from [something else].

And I notice that when somebody says something like we need to organize now to get better candidates for the next election, somebody will inevitably reply there isn't going to be a next election, we're totally cooked. Anyone imagining a future state of improvement will inevitably hear that the future holds only despair.

These are of course just examples to describe a dynamic that applies to a frightfully wide range of possible actions and reactions within the discourse, but I think you get the picture. If you've seen it, you've seen it. Nothing about today's fascism is especially bad today because it's always been bad and it's always been this bad; the way you're opposing is a useless performative distraction and you should be ashamed of it; we've lost already and we're doomed. Et, as they say, cetera.

Do these example responses contain some element of truth? They do, actually.

Are the responses offered in order to express that truth? I'd say frequently they are not.

When I or somebody like me does this, it is like a tall guy at a play or concert who is blocking everyone's view but isn't even facing the stage, which, I mean, my god, is there a bigger asshole than that? (Particularly if he won't stop whistling?) In this posture, I sense a motivation to cast oneself as the most knowledgeable not about the light but about the darkness—as if acknowledging the darkness must involve denying even the existence of light. This strikes me as a foolish way for a person who is privileged by supremacy to behave, and also a very supremacist posture to take for matters pertaining to fascist darkness and the light of humanity that overcomes it.

What, then? Why say these things?

Or don't subscribe. I'm not the boss of you. But if you do subscribe, my gosh the splendors that await you.

While it is true that the fascism we see rising in the United States springs from a deep well of traditional and foundational white supremacy, it's also true that fascism is on the rise ... which means that there is a progression happening here, a determined effort to move us from something better back to something worse, which means that we had at some point moved from something worse to something better. When I see an it's always been that way response—specifically from a person who is similarly advantaged by American traditions of supremacy—I often detect not a motivation to cast light upon the realities of supremacy's historical presence, but a motivation to deny that any progression is possible, to flatten history's tides of progression and regression into a stasis of stagnation, with supremacy unified, unchanged, and unchangeable—I suspect because if this moment is not uniquely dark, then this moment is not asking anything special of us; no particular moral mandate has been issued, there is no new discomfort to enter, there is no new cost to pay. And I would observe that white supremacy is, above all, opposed to discomfort and to paying costs.

And while it is true that many people who act in opposition to rising fascism often behave in performative and self-interested ways that betray a shallow understanding and suggest a lack of moral clarity or endurance or reliability, it's also true that we desperately need opposition to fascism ... and there is awareness happening here, however fleeting or ephemeral, a reaction against something unacceptable. I wouldn't ask a marginalized person who has learned how shaky new white allyship can be to put the full weight of their truth on such awareness, but I do think it might be incumbent upon we similarly privileged people to take that risk. When I see a this is all useless performance response—specifically from a person who is similarly advantaged by American traditions of supremacy—I often detect not a motivation to cast light upon a better way and invite a person of weak conviction and limited capacity for outrage against injustices into a greater determination and an expanded capacity, but rather a motivation to negate any determination whatsoever, to muddle all awareness and conviction into an undifferentiated puerile gruel of insincere cringe—I suspect because if people newly awake to the dangers of fascist supremacy cannot be trusted at all, then there is no need to do the work of bringing them along, and if taking even the smallest most performative action is worthless, then there is no need to take even the smallest most performative action. No particular moral mandate has been issued, there is no new discomfort to enter, there is no new cost to pay. And I would observe that white supremacy is, above all, opposed to discomfort and to paying costs.

And while it is true that fascism's hold is frighteningly strong and growing stronger, and while it is true that they certainly intend to demolish democracy until not one brick lies upon another (we've never been a democracy, it has always been demolished I hear somebody say), and while it is true that the demolition has been ongoing for some time now, it's also true that we are going to need to use every lever we have in this fight (voting just makes you feel good, but go ahead and post your little sticker on social I hear somebody say) ... and there really are systemic levers that can be used to push back traditional American supremacist fascism, which I know because they have been used before to do so. When I see a we've lost already response—specifically from a person who is similarly advantaged by American traditions of supremacy—I often detect not a motivation to call people away from less impactful activity to more impactful activity, but rather a motivation to suggest that no action can ever have an impact—because, I suspect, if no activity can have any impact, then no action will be required; if we're totally cooked already, then there is no further price that needs to be paid and no reason to not simply seek one's own comfort. No particular moral mandate has been issued, there is no new discomfort to enter, there is no new cost to pay. And I would observe that white supremacy is, above all, opposed to discomfort and to paying costs.

These are behaviors that center the darkness rather than the light. They don't make light, and they don't reflect light; instead they make an obstacle to light. A boulder in the road. A total eclipse of the sun. It seems to me that such a thing is more unaware, more performative, and more ineffective than even the most unaware, performative, and ineffective show of opposition. It's a posture that not only doesn't try to shine light into the darkness, but opposes even the idea of trying.

Sometimes these reactions are purposeful attempts by malicious people to snuff out hope and awareness and conviction, but I believe more frequently they're instinctive returns to a habitual supremacist mindset that is dedicated above all to comfort without cost and reconciliation without reparation. I think they reflect a desire to be credited for awareness and conviction without having to accept the moral imperatives that awareness and conviction bring to actually move on to the costs of maintenance of the good we've inherited and repair of the brokenness we've inherited.

As light offers an unmistakable point of distinction and differentiation from a fascist darkness, which can inspire more people to become more light, and more, and more, so an obstacle that blocks the view of light naturally will diminish those effects, and assist the darkness.

I think we'd do well to not be obstacles; we'd do better to demolish them.

We should be stars instead; lights in the darkness that the darkness cannot overcome. Or, if we don't have that in us, we should at least be moons that reflect the light we see, rather than moons that obscure it.

So here are a handful of brief thoughts on how to do that.

Another quick interruption to scroll quickly past before you continue the essay.

The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work and pay whatever they want. Why would you pay for something that is free? Click the button; answers await you.

Recognize the utility of earnestness.

There's a certain cringe factor to wanting to make the world a better place—isn't there?—especially if the person expressing it is new to the concept and clumsy in their action and language. It's far cooler to be the one who so completely sees the totality of the corruption around us they can't be touched by it than it is to be the one who has been coddled their whole lives and now finds themselves shocked by the revelation of the world's corruption, yet desperately hopeful that what is broken might be fixed and eager to help make it so. And yes, this sort of earnestness is often shallow, and yes, often self-centering, and yes, often fleeting ... and still, even a shallowly ignorant earnest belief in progress and improvement will accomplish more than a lazy cynical belief that progress and improvement are unattainable. Earnest belief is what creates more earnest belief. Cynicism, meanwhile, only works to help ensure that earnest belief will be fleeting, that the shallows will dry up instead of running down to greater depth.

It seems to me even the most shallow earnest hopefulness, or the most naive hope that things should get better—and more, might actually get better if the attempt is made—will never be as shallow and complacent or naive as a cynicism that says things won't get better and never have before, and never can in the future, and casts hopeful people as fools for believing otherwise. I'd rather work with those who see work as worthwhile—because the work is so vital and desperately needed. Even when hope is clumsy and new and unsophisticated, I still think it understands better matters of light and darkness better than cynicism, and can serve to us a needed reminder that this was once all new to us, too—and not that long ago.

Find your mission, let others find theirs.

This could be its own essay. I will explain. But no, there is no time; I will sum up. For those who have progressed from the complacency of cynicism into actual hopeful action, there is a tendency to find a mission. This seems natural; there is so much that is broken today, and the white supremacist forces arrayed against repair are powerful. Anyone who tries to take it all on doesn't just risk becoming overwhelmed and burned out—they make burnout inevitable. Mission is what's needed. If mission isn't a helpful word for you, you might think of focus. You will do these things, you will not do those things. People bring what they have to offer to the moment, and find a place where they seem best suited to help. I think this is natural and appropriate.

There's another tendency, though, a mistaken and self-serving one; the tendency to believe one's mission is the only mission, and that all others are distractions, leading to the conclusion that anyone else engaged in some other activity is wasting time and distracting energies that might be better spent on your activities.

Some people are working primarily on the legal fight against unconstitutional white supremacist power-grabs, others work primarily with strategic civil disobedience, others work to organize within the Democratic party structure we have, such as it is (I think here not only of primary and general campaigns, but calling campaigns, letter campaigns, petitions, and the like) while others may work to organize politically outside that system. Some lead and organize demonstrations, others lead and organize food banks and mutual aide networks. Some are working to call attention to the plight of people suffering in Gaza, others on the plight of people suffering in Ukraine, or Congo, or right here in the United States. And, if you're a savvy type, you're probably thinking hold on a damn minute, Moxon, these aren't mutually exclusive activities—a lot of people do many of these things at once.

True and good point, entirely rhetorical person I just made up! People do and should do as much as they can, and I have observed that when you start to act, you often find more capacity for more action. So yes, missions can expand their initial boundaries, but still every mission will have its boundaries. The trap we fall into is believing that people working outside of the boundaries of our mission are wasting their time on distractions, rather than working on their own mission.

Somebody is organizing within their church to change the church from within? Somebody is organizing a Tesla protest? Somebody is knocking on doors for a candidate? Perhaps those things aren't part of your mission. If so, they would indeed be a distraction to you if you were to do them, because they aren't where your mission lies right now. But they aren't a distraction to them; in fact, these things that might distract you may well be their mission. We might just need churches joining the fray even if the institution of the church is badly compromised and complicit right now; putting economic pressure on the oligarchs that have bought our political system might weaken them; and having better candidates in elections may help preserve our democracy even if it is teetering, or to rebuild it if it has fallen.

So I have learned when I encounter such things to remind myself that not all missions are mine. Most of all, I remind myself that if I spend my energies admonishing other people because their strategies are not the same as my strategies, I'm wasting my energies admonishing them instead of focusing on the work at hand, and I am inviting them to waste their energies responding to me.

And that makes me the distraction.

Keep despair out of circulation.

I should be careful to define what I mean here. These are desperate times, and I think for most of us despair is often nearby. I'm not saying "do not feel desperate," and I'm not saying "don't talk to others about your feelings." We're going to need to count on each other now. We're going to need to carry those without the strength to walk, and we're going to need to watch out for people who might not have another step left in them but don't know who to ask for a hand. So please find your people, and let them know when the wolf is at your door.

I'm talking about something different, something particular but common, which is to put despair into circulation. This is an act that doesn't seek help from a place of desperation, but rather seeds despair into places of hope. This is the instinct to respond to any desire for action with the reason the action will fail; to anticipate the fascist response to any tactic and grant them the victory before the attempt is even made. It's the instinct to run and hide from the moral imperative to fight. It's a call to forfeit the game before it starts; to not even take the field because the other team is better funded, seems stronger, and cheats.

To be blunt, I think it's a way that people have of making themselves feel better when they aren't doing much of anything to help and know they ought to, but would rather not. It makes sense, in a way. If there's no use in trying then you don't have to try; if you've already lost the fight then you don't have to fight—so you make it a point to tell everyone who's still trying and fighting the bad news. It's not a helpful way to be, but it doesn't cost a thing, which I think is the point of it.

Don't be that person. When you are you're not opposing supremacy; you're participating in it from a slightly more knowledgeable place.

Hey OK that's all I had to say. Be excellent to each other.

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries and the essay collection Very Fine People, which are available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He's got his night shades on.

Comments ()