How To Talk Politics At Thanksgiving

Using story to distinguish between intent and reality.

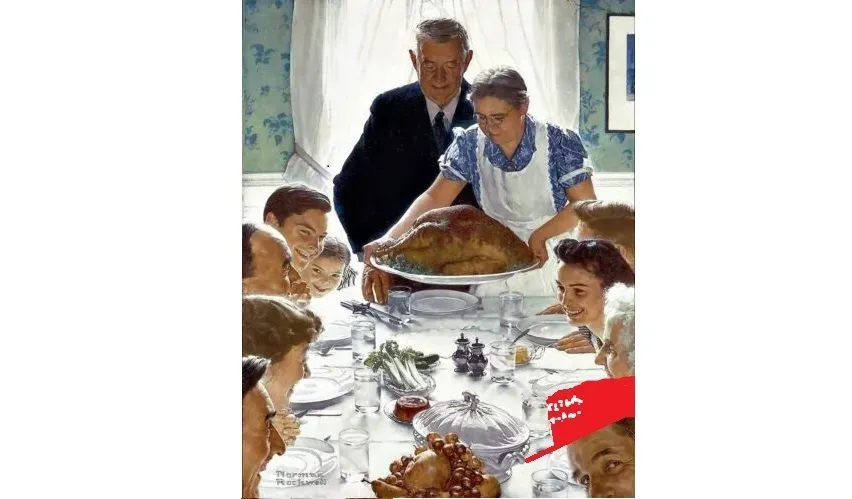

OK! It’s Thanksgiving Day, which is a day to give thanks, and also apparently a day to decide how you’re going to deal with political conversations around the dinner table.

There’s a regular cottage industry (which I believe is an industry that can make enough money for you to afford a cottage) that’s sprung up in recent years, writing annual instructions about how to keep the peace in these polarized times during family dinners. It’s a common theme, and it’s easy to see why; we’re all in each other’s lives, and at least some of us believe absolutely horrible things, and nobody can agree who it is that believes something horrible.

And who could blame people for wanting to keep the peace? Personally, I am not a fan of strife at a feast, nor do I not seek it. However, it may just happen that somebody raises an opinion up with which you will not put. And then what to do? People want to know. Hence, many articles about how to deal with Racist Uncle or Liberal Cousin or whatever.

This one is mine. Hey, I want a cottage too.

Look for these primers; they’re everywhere. The Heritage Foundation, a think tank that has architected the rough beast now known as modern conservatism, put out one of their own, one that recommends that you seek common ground with your familial libs, by explaining that conservatives “care just as much as [liberals] do (maybe more) about clean air and water, helping the poor, ensuring no one goes without needed health care, and creating jobs so everyone has a chance to live the American Dream.” And then it goes on to say that progressive politics fail to create those things, so, sadly, they cannot support progressive politics, alack, alas.

We could argue any number of those points, I suppose. But no, let us seek that common ground. The point Heritage is making is that everyone intends for everyone to have those good things, and that conservatives actually even intend it more.

Intentions are the best, aren’t they? What’s fun about them is the way you can separate them from what actually happens, like turkey skin sloughing off of a perfect slab of white meat.

So that’s cool. It’s nice to know that everyone cares so much about good things, and apparently wants good things for everyone. It’s great to understand how much good intention is wafting around the dining room along with the turkey smells. And who could fail to be charmed by somebody who can’t help themselves from suggesting—while seeking common ground—that not only are they as good in their intentions as you, but they are actually probably better?

And this suggests to me a way you can talk to people who are in your life who care just as much as you do (and apparently maybe even more) about the things you care about, but who you can’t help but notice just so happen to be supporting people and policy that are actively destroying all those things.

As a caveat: I don’t think this will work in the slightest, if your goal is keeping the peace or changing anybody’s mind—but then I think everyone is responsible for changing their own minds, and I don’t see argument changing minds. But then again, I think a mind only changes if it opens itself to the possibility of changing itself, and if there is a mind that has opened in such a way, argument in opposition is going to help it along far more than a polite silence.

So really what I’m saying is, if you don’t care about keeping the peace, this probably won’t change any minds, but it might be fun for you personally. If your goal is keeping the peace, just chew your inner cheek and grip the table. Time will pass; it always does.

Here’s what I recommend.

I’m publishing a book of essays, and my readership is helping me do that. If you want the details on how you can get in on that and get a signed copy and my thanks in the acknowledgements, click this link.

(If you do not want the details on how you can get in on all that, click this link instead.)

First, find that common ground. Acknowledge that we all agree that we care about good things, and for everyone, but we also seem to agree that at least some of us, despite our intentions, apparently believe horrible destructive things. Not who it is that believes horrible destructive things, of course, but just that some of us apparently do. And then acknowledge that yes, they probably care even more.

Next, ask them about their favorite stories. Stories aren’t about intention, really. When you tell a story, you can start with intention, but eventually you’re going to get into action or there’s no story. So, stories are about what actually happens, which will be useful later.

So, ask. Ask about favorite stories. Movies, books, parables, whatever. Hear them out.

Finally, dig in. Thank them for all the story recommendations.

Now ask them about their favorite stories where people do the sorts of pragmatic, grown-up things that their preferred policies and politics actually enact. Not the things they claim to intend with the politics, but the things those politics actually do.

Ask them to tell the story where heroes build the world they insist upon, in other words.

Ask them for their favorite story about the brave rich country that saved their society by building a wall around itself, to keep all the dirty poor invading hordes out. Ask them for their favorite story about the people who wisely separated the children of refugees from their parents, to better dissuade any other refugees from coming.

And then maybe ask them for their favorite story about the country that was brave enough to do whatever it took to feel safe, even going so far as to praise torture.

Or their favorite story where a heavily militarized police force kept the impoverished neighborhoods they occupied perfectly subdued, on behalf of neighborhoods full of wealthier citizens who received a greater share of resources.

Or their favorite story about a cop who killed a kid, or a well-fed vigilante who kept everyone safe by choking a homeless man.

Ask them for their favorite story about how a dominant cultural and military superpower harnessed power and law and might to successfully prevent the group it was oppressing from being liberated.

Or their favorite story about a heroic strongman, who called journalists the enemy, who referred to his political opponents as “vermin” and vowed to expunge them from the country.

Or their favorite story about a billionaire who bribed a judge, or their favorite story about a bribed judge who overturned civil rights legislation, or who sued a journalist for exposing his corruption, or who defunded a public works project to protect his business interests.

Ask them for their favorite story where the heroes targeted a marginalized people group for exclusion and harm.

Or their favorite story about library closings and book bans. Their favorite story about defunding school systems.

Or their favorite story about a high school bully who bullied a kid for being different, and the teachers who took the bully’s side, in order to make “normal” kids feel comfortable.

Ask them their favorite story about people who valued property more than other people, and profit more than life, and how much money they all made, and how they won out over the guilt trips other people laid on them.

Or their favorite story about a rich man who got a tax break and defunded schools and programs for those in need.

Or their favorite story about a rich woman who taught poor parents a lesson by making sure hungry children didn’t get free lunch.

Or their favorite story about a boss or a landlord who kept so much of their profit for themselves that they forced their employees or their renters to take second jobs.

Or their favorite story about an insurance company that maximized profits for its already wealthy shareholders.

Or their favorite story about a rich hero who owned and ran profitable prisons. Or their favorite story about a country known for imprisoning more people than any other.

Ask them for their favorite story about a politically empowered minority who forced other people to live according to their religion.

Ask them for their favorite story where the heroes made sure that only the deserving hungry got food, where only the deserving sick got care, and then only if it could be afforded.

Tell them they can use their Bibles, if they want.

Here’s a little thought about our current divide, which I suppose is a “political” divide insofar as politics is how it is carried out.

What's happening is a critical mass of people are done putting up with abusive bullshit anymore—taking it or excusing it—and I think this seems very divisive and dangerous to people who rely on abusive bullshit for either fortune or identity.

To demonstrate this—at Thanksgiving or at any time—I look to story.

What I’ve noticed about abusive people is that they always make themselves both the victim and the hero of their own stories. They are heroes of good intention, victimized by people who actually expect them to enact their stated good intentions as good policy, and who cruelly and unfairly notice when they do the exact opposite of what they intend, grasping as much good for themselves as they can by making sure none of it comes to others.

So they have to tell a story where pure intent justifies any action. You can do this as long as you keep the bullshit spinning, but what I’ve noticed is that if you actually put a character who does those things onto the page or screen, they come off as a real asshole.

What using story does is expose why people of bad faith can’t tell their own stories as stories. The reason is, the person is operating with ostensibly good intent but in observably bad faith—because what we put our faith in determines our actions, and actions are how one can determine true intent.

And story reveals the difference. It’s one of the great uses of story, in fact.

What using story demonstrates to people aligned with abusive power is that they can’t tell their own stories—not really.

A story of power defending its power? Of privilege defending its privilege? You can try to tell a story like that, but you can’t really sell it.

Not around the dinner table.

The Reframe is supported financially by about 5% of readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and is co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He’s just a box of rain.

Comments ()