The Man In The River

As a brief interlude in a series on the national current, a parable of a wise man

Once there was a wise man, who travelled to strange lands, and as he travelled, he came to the bank of a winding river. Edging the bank were houses, set at distances from one another here and there. The wise man walked upstream, watching the slow current carry leaves and twigs past him.

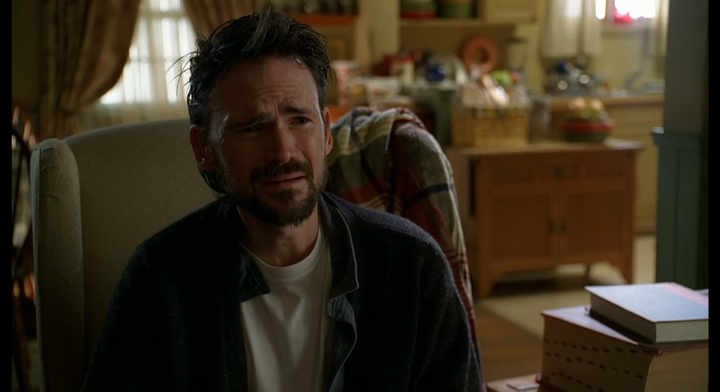

In time, the wise man came upon a man who sat in a chair in front of his small house.

“It’s a pleasant day,” said the man in the chair.

“All days are pleasant in their own way,” observed the wise man.

“I can see that you are very wise,” the man in the chair said with a smile.

“How will you spend this pleasant day?” the wise man asked.

The man in the chair shrugged. “I expect I will sit in this chair and enjoy the warmth of the sun,” he said.

“Will you enjoy the river?” the wise man asked. “Will you fish its banks or swim its waters?”

A shadow passed over the face of the man in the chair. “No fish swim in my part of the river,” he said, “and I dare not enter. The water is badly polluted and unsafe to touch.”

“How can this be?” the wise man inquired. “The water is perfectly clear.”

The man in the chair shook his head sadly. “I’ve learned not to explain it,” he said. “Wise men pass by here most days, and I have learned that they prefer to see for themselves and draw their own conclusions based on their own perceptions.”

“Indeed, I have found that seeing for oneself without one’s opinion clouded by that of any other is the only path to true knowledge,” said the wise man.

“If one’s sight is clear,” said the man in the chair, “I suppose that may be true. If you travel around the next bend, you will come upon a sight that may explain the matter, if you are able to observe.”

“I live for enlightenment,” said the wise man.

“Then may you find it,” said the man in the chair. “It is a remarkable sight that even a fool could understand—and, as I have said, I frequently encounter wise men, so I know them well, and perceive that you are a wise man, not a fool.”

“I will go and see this sight,” the wise man said.

“Return to tell me the answer,” said the man in the chair, “if you think you have found it.”

The wise man continued upstream until he passed around the bend, where he did indeed come upon a remarkable sight: a man was in the river, pulling by a chain into its center a barrel marked TOXIC WASTE.

“Sir,” the wise man called. “Perhaps you should not be in the river. I have it on good authority that this water is polluted and unsafe to touch!”

The man in the river snorted derisively. “I see you’ve been talking to my neighbor,” he said. “I assure you that this water is perfectly safe, the most exceptional water in the world!”

As the wise man drew near, he spied hundreds more barrels floating in the river, somehow secured against the current. The man in the river dipped beneath the current, affixing the barrel to some secured point in the riverbed. When he emerged, he climbed atop the barrel, and the wise man could see that his skin was red and raw and blistered, as if burned.

“Your neighbor assures me that the water is badly polluted,” the wise man said.

At this, the man in the river became as livid as his skin. “ALL HE DOES IS LIE!” the man in the river screamed. “HE POLLUTES THE RIVER! HE POLLUTES IT EVERY DAY BY PULLING BARRELS OF WASTE INTO THE RIVER, THEN RELEASING THE WASTE BY PIERCING THE BARRELS WITH A GIGANTIC HOOK!”

As the man in the river made this startling pronouncement, he produced a gigantic hook and pierced the barrel, which released a great spray of clear but foul-smelling liquid into the water.

Wishing to escape the noxious fumes, the wise man walked back downstream to the man in the chair.

“I am assured that the water is perfectly safe,” the wise man said. “The most exceptional water in the world.”

“I see you’ve been talking to my neighbor,” said the man in the chair. “I assure you that the water is polluted. Have you detected the cause of the problem?”

“I think that I have,” said the wise man. “I think the problem is that you and your neighbor are very polarized against one another, which has caused you to distrust one another and think the worst of one another.”

“I can see that you are very wise indeed,” said the man in the chair. “I am only a fool, so I think the problem is the pollution of the river.”

“Yes, but don’t you see that your neighbor says that you are doing it?” the wise man asked. “And he seems most badly harmed by it. Perhaps he knows something about it that you do not, that you could learn if you listened to him.”

“All he does is lie,” the man in the chair sighed. “He pollutes the river. He pollutes it every day by pulling barrels of waste into the river, then releasing the waste by piercing the barrels with a gigantic hook.”

But the wise man, who was very perceptive indeed, just clucked his tongue sadly, and smiled. “You know,” he remarked, “he says the exact same thing about you.”

“So I have been told,” said the man in the chair with a sigh.

“Don’t you see, my friend,” said the wise man, “that to an impartial outside observer such as myself, you and your neighbor sound exactly the same?”

“Do you see no difference at all between us?” asked the man in the chair.

“None whatsoever,” the wise man said. “My poor friend, if only you could hear each other! You both used the exact same divisive words about one another—phrase for phrase. Anyone can see that it is your words that divide you.”

“I see,” said the man in the chair. “What do you propose I do?”

“Meet in the middle,” the wise man said.

“The middle of what?” asked the man in the chair, who seemed bitterly amused for reasons the wise man could not fathom. “The middle of the river?”

“Any middle will do,” said the wise man. “The main thing to realize is that in any conflict, the answer can always be found in the middle.”

“This is why I’ve learned not to explain these matters to anyone except fools,” the man in the chair said, and he closed his eyes. “What you have told me is the exact same thing I hear—phrase for phrase—from most wise men who come by, particularly if their wisdom has led them to prefer to trust only to what they can see for themselves.”

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He’s twelve stories high, made of radiation.

Comments ()