Two About The Atmosphere

Bridges and bombs, aggressors and fights. Or: how to change the atmosphere, and why.

Note: this essay was originally published on Revue on March 20, 2022.

I want to pick up from last time.

Well, no. Last time was a LOST recap that got downright biblical.

But last time before that, I talked about a framework of communication and human change that I’ve found useful, describing three levels of possible impact: action, attitude, and atmosphere.

That last post was one about the atmosphere.

This will be two about the atmosphere.

Last one was about defining the current atmosphere.

This one will be about changing the atmosphere.

So now: a story.

____

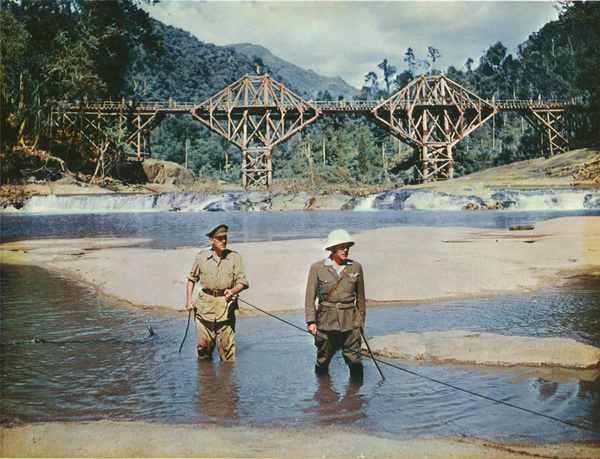

Three weeks ago, a man blew up himself and a bridge.

The end.

____

That’s one way to tell the story. Now let me tell it again.

Three weeks ago, the Ukrainian army determined that the Genichesky Bridge in Ukraine had to be demolished, to slow the advance of tanks and troops in the invading Russian Army. Ukrainian Army Engineer Vitaly Skakun Volodymyrovych volunteered to place the mines, which exploded before he was able to safely escape. The bridge was demolished, and Volodymyrovych died in the blast. The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine of Skakun in a Facebook post had this to say:

His heroic deed significantly slowed the advance of the enemy, which allowed the unit to redeploy and organize the defense.

The end.

___

I have some observations.

First I want to acknowledge that, while I’m going to use this story to discuss some concepts and ideas in the abstract, this is a real story about a real person who really died, so it’s important to acknowledge that for Volodymyrovych, his family, his friends, and other loved ones, this is not in the least abstract; it is a horrible and personal tragedy.

It’s also worth mentioning that a) war is a tragic and criminal failure of imagination and spirit on the part of those who, through deliberate aggression, force it to exist—a construct, which, by its very function and intent, creates thousands or millions of such tragedies; b) people who force war into being deserve both our scorn and the severest consequence possible, while people who exhibit the physical bravery necessary to protect those threatened by war’s grim intention from those whose intent is war deserve our honor and awe, which means that c) while war inevitably creates atrocity indiscriminate to side, in war there are also generally aggressors, and recognizing who the aggressors are matters greatly in our assessments and discernments of those who fight in wars, if we would be moral people.

Now, for some thoughts about the story that are a bit more abstract:

1) Bridges are usually miraculously useful feats of engineering that connect people to one another and make passage that would otherwise be difficult or even impossible easier, and bombs are usually vile and malicious feats of engineering designed to bring chaos and destruction to that which ought to be preserved and protected. Usually a bridge should be preserved and maintained, any person who would neglect the maintenance of a bridge would be considered a dangerous fool, and any person who would destroy a bridge would be considered a monster and a terrorist.

2) Sometimes a bridge is the thing connecting aggressors of direct and present abusive and even violent intent with the people they intend to harm and kill, and therefore sometimes bridges need to be destroyed, and the person who destroys such a bridge would be seen as a hero who has undertaken a significant risk, or even paid the ultimate personal sacrifice, to create a necessary separation between the two.

3) The difference between 1 and 2 is, quite simply, the difference between peace and war, justice and injustice. And while we always hope for peace, working for peace requires a recognition that bridges between two positions, like all cases of human connectivity, don’t cause peace, they are the result of peace. Neither will war be prevented by refusing to demolish a bridge connecting aggressors who intend to bring war with those to whom they intend to bring it. In fact, such a refusal will speed war in a way that favors the aggressors.

4) The victims and targets of war don’t get to choose war—the aggressors choose it for everyone, and then it becomes a fact. Everyone else gets to choose only what to do about it.

5) Untargeted observers of war also don’t get to choose war—but they do have to decide whether they accept the aggressor’s rationales for bringing it, and whether and who they’re going to help—including how they’re going to react to any demolished bridges they see, and how they are going to talk about those who demolish them.

I ponder these abstracts, during a time when Republicans in state after state are passing laws that aggressively target trans people and gay people and women and Black people and sick and disabled people for minimization and disenfranchisement and oppression, and harm and abuse and terror and death—and are even in some cases are trying to make it a crime to leave those states in order to escape the fate the drafters of these laws have in mind for them.

I didn’t link to all the stories of this happening. I’d double the length of this essay if I did. Not the paragraph: the essay. More examples are coming.

I ponder these abstracts, in a time when many people seem dedicated, above all else, and in the name of civility and health, to respond to these abusive and horrific outrages by maintaining existing bridges and building new ones—from those who would harm our friends and families, to those who would be harmed.

I ponder these abstracts, in a time when we can all see our fathers strangling our siblings to death, while the only observation some people seem capable of making is “both sides are fighting, and fighting is bad.”

Remember: I told you the story of the bridge and the bomb twice.

So you see: It’s not the story, it’s the telling.

It’s what you leave out of the story.

It’s what you keep in.

I’m aware that there are people whose ability to process abstract points is either naturally limited or deliberately curtailed, so I suppose I had better make something clear: I am not saying that, in response to Republican lawmakers and their evil and fascist predatory laws, we should bomb bridges—or bomb anything for that matter.

In almost no cases do I think bombing is good. I say almost, because I remember Ukrainian Army Engineer Vitaly Skakun Volodymyrovych, and I realize that sometimes, when an aggressor goes far enough, it does get to that point.

To make a related point, I also think it is almost never OK to cut a person’s sternum in half and split their ribcage open like they are a Thanksgiving turkey. But sometimes there’s a heart in bad need of immediate extensive repair, and there is a skilled surgeon on hand, and not cutting the chest open is the far more deadly option.

I hope you don’t take from my approval of open-chest heart surgery that I favor flaying people. So it is with my approval of a demolished bridge. It’s very situational, but useful for analogy, especially if I’m pondering the bridge-builders and emergency ignorers of our present fascist age.

What I’m saying is this: some things are health, and some are only the result of health, and it’s important to know the difference.

A bridge is the result of a healthy and peaceful natural human system. It doesn’t cause health and peace. It arises from health and peace, and makes a present state of health and peace even better.

In much the same way, being able to disagree over political manners while maintaining normal and unaffected social relationships with the person with whom you disagree is a result of a healthy political climate, not health itself.

If my political belief is that you or the people you love (or really any other people at all), don’t exist enough for their lives to matter, or that such people should not be treated as if they exist, or should not be treated like an equal person under the law, or should not be protected from systemic harassment and terror … then maintaining a normal relationship with me no longer represents health, but rather a deep sickness.

And that’s true even if I say that that of course I don’t believe in all those horrible things or want those grim results, when you can see that what I actually do is lend my support and energy and practiced ignorance to efforts that create and entrench systemic harassment and terror for you or others.

Yes. And why am I bringing this up?

Because confusing the manifestations of health with health itself is one of the dominant attributes of our atmosphere.

And remember, we want to change our atmosphere.

We want healthy things. We want a world of bridges. We want a world of easy and normal relations, when we can have rational disagreements with one another about how to solve problems, not because we enjoy disagreement, but because we actually agree what the problems are.

We want a world of comity.

We want a world without fights.

But these things are the signs of health. They aren’t the cause.

And there are people who will use our desire for healthy things to encourage us to keep all the signs of health in place, so they can harm all the people they want to harm.

I’m not writing to any of them. They chose to bring war to their chosen targets and victims, and continue to bring it long past any point of plausible deniability. I’m going to pay them the respect of believing they are who they’ve shown themselves to be, the respect of believing they want to do the things they are presently doing.

They can go fuck themselves.

I’m writing to you: the person who sees the intent and the harm and wants to help.

I think the way to help is to change the atmosphere.

You change the atmosphere with new ideas.

So: now for some new ideas.

____

It’s worth looking at how atmosphere changes.

Last time I ended with a few thoughts about atmosphere:

1) Atmosphere is only changed by ideas—specifically new ideas.

2) The best impact you can make on atmosphere is your alignment with new ideas. You can change your own mind, in other words, not those of others—so it is your own mind that is your responsibility.

3) You don’t solve problems by cooperating with people who want the problems.

Perhaps you’re like me. Perhaps you’d like to change the current atmosphere, which appears to be leading to collapse on multiple fronts.

I’m going to give you three new ideas, in a particular order.

1) Every human being is a unique and irreplaceable work of art, carrying intrinsic and unsurpassable worth.

2) Violating the first rule, or belonging to an organization whose energies are devoted to doing so, is absolutely unacceptable.

3) To find something unacceptable means you are compelled to fight it.

Now: I’m aware that these aren’t exactly new rules. In other words, there have been people throughout history who actually believe these things, and lived that way, and changed the atmosphere by doing so, at great risk and cost to themselves.

And there are still heroes like that today. They’re hated and feared by today’s aggressors—the same aggressors who claim to revere yesterday’s heroes, now that yesterday’s heroes have been murdered by yesterday’s aggressors.

But if you look at what actually happens, and how our power flows, and the structures that exist to support it, and what people actually support, you’ll find that these are three ideas that don’t exist in our current atmosphere; and the trace elements that do exist there are being treated by the current atmosphere as an anathema and an invasive force … which they are.

Aggressors use aggression to change the atmosphere. They understand what it means for the atmosphere to change, and they’re fighting to prevent it.

And yes, we’ll need to fight to change it, which is not the same as saying we must be violent. Not all fights are violent, and not all fights are external … but we will need to fight, and fights always have a cost.

Remember: the impact you can make is the impact on yourself; your alignment with (or against) the current dominant ideas and your alignment with (or against) new ones—and what new ones you choose to align with.

Align yourself with dominant old ideas, and you’ll help keep the atmosphere the same, which will govern the attitudes that operate within it, and define the actions that are possible within it.

Align yourself with the new rules, and against the old ones, and you’ll change the atmosphere.

Working on attitudes is good, and there are people who are great at it. We should all think about the attitudes with which we approach life.

Working on action is good, and there are people who excel there. We should all engage in useful direct actions within our present reality.

I’ve come to realize that almost all my work is focused on the atmosphere. You might say I focus on a “reframe.”

There are a lot of reasons I find it compelling to do so.

Notice what focusing on atmosphere does: it opens and expands. It doesn’t prescribe specific actions to a general audience that might find themselves in vastly different circumstances from one another; rather, it presents ideas that can be applicable generally and to a vast array of expressions and skills and situations.

It presents the ideas, and then leaves the actions and attitudes open.

Some of you might exist in a position of authority and influence, and your job might be to spend that capital to impact policy, or to promote new thoughts to a large audience—conveying the message that all people are art, and that behavior, belief, action, and organizations that degrade art are absolutely unacceptable. You might hold such authority that you can change the alignment of systemic consequences and incentives away from the current atmosphere of dominance and supremacy, and toward ones that honor the first rule and enforce the second.

If you’re somebody with that level of power and influence, you’ll know full well that doing so will involve a cost. Paying that cost is your job.

Some of you might be human works of art who are, by unavoidable circumstance, currently surrounded by people who in many ways have no regard whatsoever for the existence of people like you, and your job might simply be to stay alive in fraught circumstances, in the full realization that the suffering and depredations you suffer are absolutely unacceptable—even if they are currently being accepted by people around you.

If you’re somebody in such a perilous situation right now, you know full well that just staying alive is a fight, and what that fight costs.

Those are the extremes.

There are a lot of people living in between these poles.

You probably live there. I do.

(An aside: this is why I find it frequently useless, when I’m in the middle of trying to change the atmosphere, for somebody to demand that I lay out my detailed policy plan. Those are actions, and they aren’t actions I am situated to take. Asking me for a 12 step plan is to treat me like a politician—something I’m not—with the power to enact policy—which I cannot do. And it’s usually proffered as a way to simply try to negate the slight change in atmosphere I’m bringing by expressing a new idea.)

A few other thoughts about changing the atmosphere. Let’s recap the new ideas:

All people are art.

Anything that degrades human art is unacceptable, and supporting organizations that exist to do so is unacceptable.

A lot of people will think by “organizations” I mean the Republican Party, which I surely do—and that needs to be unpacked at more length than I’ll get to right now—but it’s not only the Republican Party that systemically and structurally degrades human art.

A lot of people will think that by “unacceptable” I mean shunning people for what they say or do or intend or align themselves with, and to that I will say, yes, absolutely, it might mean that—provided doing so honors the first rule. Sometimes a bridge needs to be demolished to keep somebody with violent intent from the people they intend to harm. And sometimes separation is what is needed for health.

But sometimes, if you are currently unthreatened, the braver thing is to divert an aggressor to the bridge you’re standing on—which means away from those who are currently targeted for harm.

Sometimes it might be bravest to let somebody know something like this: “Hey. I can’t help but notice what you just said, did, or supported. As somebody in your life, I need you to know that a core operating principal for me is honoring the humanity of all people, and I want you to know that what you are saying, doing, and supporting violates the essential humanity of many people, including yourself, and I want you to know that I find that absolutely unacceptable. Knowing what I know about you and your many other fine qualities, this saddens me, and if you persist in it, it’s going to fundamentally change my understanding of who you are, and that’s going to affect my relationship with you—and I truly believe it will affect most of your other relationships as well.”

Notice that this is not a thing you are presenting as a proposition to debate, but an existent fact—information about the current state of things, and a clear consequence for continuance of the current state.

Notice that it opens a door for anybody who truly doesn’t want to harm people to learn more about why you feel that way, while leaving no room for somebody who actually does intend harm to rationalize that intent to you.

It’s not information about them, and what they have to do. It’s information about you, and what you will be doing about what they have chosen to be.

Notice that doing this is uncomfortable.

Notice that doing this will be a risk—not for others, but for you.

Notice how doing so moves you from safety to risk, from comfort to discomfort.

That makes it a fight.

So that’s one way to change the atmosphere.

And sometimes—usually, I’d say—the bravest thing to do is to look inside ourselves, to find the ways that we’re aligned to our current atmosphere of abuse and injustice, with the understanding that those alignments are unacceptable. Looking within can be difficult, and painful. Transformation can cost you something you currently have, that you’d rather not lose.

And that makes it a fight.

So that’s another way to change the atmosphere.

Those are just two examples. There are many. Infinite, in fact. Focus on the ideas, and your alignment to them. If you find better ideas than the ones I’ve presented, use those.

Notice how focusing on the right ideas will inspire new attitudes and actions.

Focusing on an idea that starts with the idea of universal human art keeps us focused on never degrading humans, even those humans who have through their vile beliefs and actions degraded themselves.

Focusing on the idea of unacceptable allows us to understand that the act of changing the atmosphere will never be a passive one, and never allows us to forget as a first priority the moral imperative of establishing solidarity with the people who are threatened by the current unjust order, regardless of the personal cost.

Focusing on actions is important, changing attitudes is necessary, but if you start with actions or attitudes, then you’re constrained by the current atmosphere.

Focusing on the level of atmosphere frees us to find new attitudes and actions, and to work on changing the atmosphere wherever we find it, including—especially—within ourselves.

Focusing on the level of atmosphere enables us to believe that things that should be different can be different, and enables us to take new actions.

And not just us.

When you do things that change the atmosphere, other people notice, and can discern those new ideas. And then they start changing the atmosphere. And the new ideas change not just attitudes and actions, but the underlying set of what actions and attitudes are even possible—even for those who don’t align with it.

And when—as is now the case in the United States and the world at large—there happens to be an attempt to change the atmosphere toward something bloody and violent, it’s important to fight that change before those aggressive efforts reach a tipping point of inevitable violence; a point when the available necessary actions become—as they have in Ukraine—either letting aggressors with violent intent harm those they would harm, or actually blowing up actual bridges, and waging actual war to protect them.

In that case, the risk we’ll have to take on will be far higher, and the price we may have to pay far greater. Speaking for what I know of myself, I say: if we’re not brave enough to take on these lesser risks now, there’s little hope that we’ll be brave enough to take on greater risks later.

We ought to lean into the ideas of universal art and unacceptable and fight now, when it’s still possible the atmosphere can change with peaceful fights.

It has to be said: there are people who intend to bring war to marginalized people in my country, which is the United States, right now—and we know that because it’s what they’re doing wherever they are empowered to do so.

They have chosen to bring it, which means that nobody else has a choice as to whether or not it exists. We can only choose how will will respond.

Some would say that this sort of talk creates a lot of unhelpful “us” vs. “them” dynamics.

My retort to that is a reminder: recognizing who the aggressor is matters greatly in our assessments and discernments of a war, as current events have amply demonstrated.

It’s the aggressor who creates the “us” vs. “them” dynamic, and once they do, then it exists as a fact for as long as the aggressor decides to be an aggressor. We can’t make it stop existing by deciding it doesn’t exist. We can’t create health by maintaining the results of health. We can only recognize the current state of unhealth, and decide what to do about it.

That includes how we operate relative to aggressors, and those they’d harm.

And it includes how we interact with aggressor’s narratives about why they are choosing to attack, and with those who have chosen to, or been tricked into, believing those narratives.

Which means we need to be careful about what bridges we leave up.

Which means we ought to finally talk about the one very powerful and popular organization in our country, which, at this point, really does exist only to degrade and harm and destroy human art—and we know this regardless of any other motivations or rationales they give, because it’s what they’re doing, as much as possible, as fast as possible, everywhere they can.

And for that, we need to talk about the elephant in the room.

That’s next time.

_____

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. He does handstands in grand fashion.

Comments ()