What Is Lost

A continuation of a series on our national current; the price we all want to avoid, and the legacy of my favorite television show

Hi.

Two weeks ago I wrote about the national current; the way it seems to flow against delivering consequences to powerful or wealthy or influential people, the way that delivering any sort of consequence to such people requires an easily observable effort—like swimming upstream, you might say—while their exoneration seems to happen automatically and inexorably, a reconciliation that is offered without requiring reparation or even any expression of regret.

And I noticed that this current is supported by voices in our discourse who seem to fear any reversal of our national current—even if they are not powerful or wealthy, even if they wouldn’t receive similar impunity, even if they are themselves often suffering the harmful effects of empowered abuse. I noted that even those who don’t benefit from a national current of abuse fear some consequence that might attend that current’s reversal.

And I ended by wondering what that consequence might be.

And this week, a majority in a body of nine—a majority whose members have proved themselves unimaginably corrupt, but who, because there exists no political will or ready apparatus to remove them, are permitted to keep making decisions governing the lives of all of the rest of us— made a decision, which is "innocent people have to stay in prison." So we can clearly observe that our systems of power exist not to establish and protect and convey justice, but to establish and protect and convey the system, and so it will remain, without a powerful sustained effort to swim upstream.

The thing about a current is, if you only swim with it, you might not even notice it, but if you swim against it, you can’t ignore it. Only once you’ve gone against a current do you know what swimming along with it feels like. It feels like ease.

And that makes me think of stand-up comedy, an art form that I love.

My favorite comic was, once upon a time, Bill Cosby, undeniably one of the best to ever do it. My dad, who had all his albums, introduced me to his work. I had Bill Cosby: Himself pretty much memorized when I was 10 or 12 or whatever. His stuff was witty and incisive and extraordinarily well-crafted. I never missed The Cosby Show, which was warm and positive and yet still hilarious—a true classic of the genre. Cliff Huxtable reminded me a lot of my own dad, who—like Cliff—was a doctor, and was usually funny, and usually wise, and sometimes gruff, but always loving. A lot of people thought of Cosby as a father figure, I think. Somebody around that time called him “America’s Dad,” and the name stuck so well that I just googled america’s dad and a millisecond later, Bill Cosby was what the internet delivered.

Maybe 10 years ago or so, my wife and I went back and showed our kids the early seasons of The Cosby Show, and, unlike many other shows of the era, it still held up. Like my father had given me Bill Cosby, I was now giving Bill Cosby to my children.

By then the rumors about Cosby were already in circulation. I think I had seen an article somewhere online, noted that it was already over a year old, and dismissed it, thinking well, if it was true, he’d have been charged with crimes by now.

No, seriously. That’s what I really thought back then, in the long-ago era of 2013, back when LOST had only been off the air a few years, and a banana only cost, what, $10?

I had that exact thought, formed with my brain, and then my brain gave that thought a cursory examination, and deemed it accurate, and then returned me to a state of not having to deal with a changed opinion of either the inherent justice of America’s legal system or the moral probity of America’s Dad. This was a state that allowed me to go on enjoying Cosby’s material in a totally uncomplicated fashion—which was, I can now clearly see, the actual purpose of having that thought.

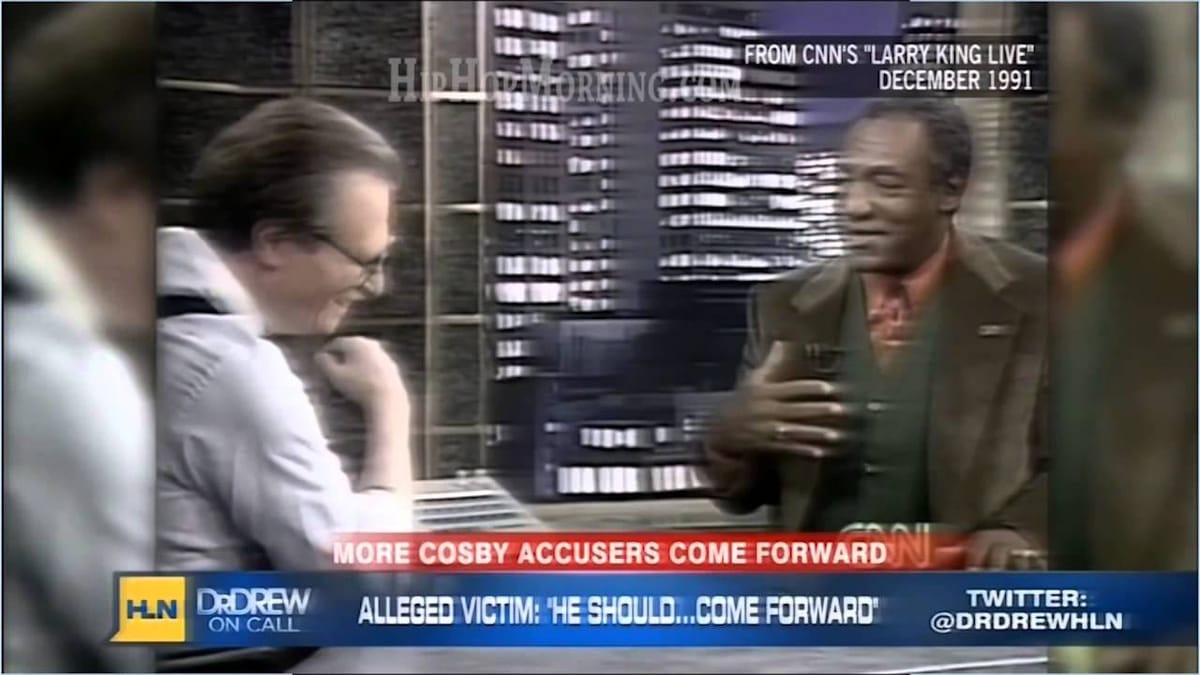

The really hard thing to process is that Bill Cosby had been telling us about Bill Cosby, Himself, all along. For example, there is a snippet from an interview he did with Larry King that you really out to go watch right now and then come back.

OK?

Its jarring how open Cosby is about it—Spanish Fly was a fairly prominent part of his act!—but also how open King is about it—the clip cuts in before we can be sure, but King seems to have prompted the topic, not to scrutinize it, but just to introduce a story he wanted to highlight as particularly amusing.

It’s almost as if drugging a woman to have sex with her—which is rape—was such an accepted practice in culture that Cosby’s use of it was notable only for his enthusiasm, and was considered so benign even in the early 90s that this enthusiasm was just another amusing aspect of Cosby’s persona, one that Larry King had absolutely no problem hearing about and absolutely no compunction about chuckling over, and one that America’s Dad had absolutely no problem telling in order to sell books.

Hello, America! indeed.

I think about this anytime somebody says of some entertainment or another “you could never get away with that today” and I think it seems like actually people do get away with that today all the time, and wonder but also, why would I want to get away with that?

Came a day that another excellent comic named Hannibal Burress called Bill Cosby a serial rapist—which is what he is—by way of criticizing Cosby for the hypocritical nature of the increasingly adversarial respectability politics he was aiming at Black youth … and for reasons that could probably be its own essay1, that single speaking of truth created an undeniable gravity that accumulated more and more and more truth around what was, we all learned, something that a lot of people had known about Bill Cosby for a very long time, until people couldn’t ignore anymore. Bill Cosby tried to simply push through all of it like he had his whole life, and went on tour, but while many people still went out to see him, more and more people had a changed opinion of Bill Cosby, and then some other consequences happened, and at last the legal apparatus even got involved, and then he even went to prison for a while, and now “Bill Cosby” means something different than it used to for a lot of people, even if his name still will come up first if you google “America’s Dad.”

It was the consequences that convinced me, I have to admit. The easier thing was to simply assume that everything was fine.

After, I had to live with a changed opinion of Bill Cosby, which meant that when I watched his material, I found that—even though it was still just as good as it had been, and I could still appreciate the craft and artistry, and understand the massive and largely salutary influence that its presentation of Black representation had on the cultural conversation during the 70s and 80s—I couldn’t enjoy it anymore in the same way, and some aspects of it, which had previously seemed entirely benign, made it almost unbearable2. And a lot of people who owe Bill Cosby their careers now have key parts of those careers associated in the minds of the public, however tangentially, however unfairly, with decades of predatory rape, and the contributions of his career upon our culture, while still undeniably real, now require an active contention with the reality of our knowledge about the monstrous behavior of the man who created it, if we wish to encounter it.

So something significant has been lost.

The question is: what is lost?

Bill Cosby lost his career and his legacy, is a way I suppose you could think about it, if you wanted to frame the whole story only around how his decades of serial rape affected him personally, which you certainly could do if you want to; I’ve noticed it’s a pretty popular way to frame stories of abuse, particularly when the abuser is successful and popular and beloved.

That’s how I lost Bill Cosby, is another way I suppose I could think about it, if I wanted to frame the whole story around how it affected me personally, which I certainly could if I wanted to; I’ve noticed it’s a pretty popular way for people to frame stories of abuse in which they aren’t the abuser or the abused party. The idea of simply acknowledging abuse, or deciding not to support an abuser’s future work, or realizing you can’t enjoy their past work, seems to be framed by those who would like to maintain an uncomplicated relationship with that work as throwing out anything good the abuser did, which seems to me the way you’d look at it if you found the abuse intrinsic to the accomplishments.

I certainly framed it that way to myself, back then: I lost Bill Cosby.

And then I thought to myself: well, at least I still have Louis CK.

No, really. I thought that. With my brain.

I’m not a world-class standup comic, so that’s the funniest thing I can tell you about this whole mess.

Louis CK was also, once upon a time, my favorite comic. He’s very good at it, in case you didn’t know. He tells a truth, but a shameful truth, and then he grins a bit—can you believe I’m getting away with saying this? But he does get away with it, because he’s expert at exuding another thing, which is the promise that he is, at heart, a good dude, which you can tell because of how honest he is being about his own shortcomings.

I say he does get away with it, by the way, because he does, even if he doesn’t have his own TV show anymore. He’s still working. He packs out arenas. He played Madison Square Garden last year, which was the same year he won his most recent Grammy.

So he gets away with it, not got. If you think that’s good, I have good news for you: you’re swimming with the national current.

I’ve learned that when I mention this, there are people will ask me: what’s wrong with that? A man makes a mistake, he should lose his ability to make a living? And maybe they have a point, but even if I let pass the reduction of what CK did to “a mistake,” let pass the idea that no longer being a successful comedian does not strip you of the ability to make a living, I have to notice that he hasn’t lost the ability to work in comedy. Certainly, people who want to continue to pay Louis CK to do comedy can and do.

I also notice that the women to whom CK exposed himself don’t work in comedy anymore. This gets mentioned less frequently by people who seem to think it important that a person should not be prevented from working in comedy because of past events.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I dismissed the first report I saw about CK, in part because it came to me on social media from a person who I often find to be a somewhat ignorant crank, but the truth is that I dismissed it because I wanted a reason to dismiss it, and my opinion about the person telling the story was a reason, so I used it. It’s a shameful truth, but it’s also a truth. (Maybe I’m skilled enough at confessing this truth I’m not proud of I can get away with it, just like my former comedy hero Louis CK does. I’m sure I can, if getting away with it is my primary goal.)

Came the day at last that the truth could no longer be denied, and CK issued a confession of sorts; so it all came spilling out and Louis CK’s movie, which had already been shot, was permanently shelved, and all the work he had done was tossed, and so was the work of hundreds of other people, and I noticed that for many, the loss of all this value was framed as something that was being done to Louis CK rather than something that Louis CK had done to everyone else.

After this, I discovered that if I watched Louis CK, while I could still observe his mastery of the craft, and I might still laugh at one joke or another, I couldn’t enjoy it in the same way as I used to. I had to recalibrate my understanding of Louis CK as somebody who was very, very, very, good at getting away with exposing himself in ways that aren’t usually deemed acceptable.

It turns out that for a lot of people, including me, the knowledge that he used his fame and respectability to abuse women meant the experience of having Louis CK expose his wrong thoughts in public just wasn’t enjoyable anymore. His little can-you-believe-I-just-got-away-with-saying-that smile no longer seemed as exonerative; it just felt more like watching a very funny guy who is very good at getting away with wrong things getting away with some wrong things by being funny. These days, Louis CK’s crowd is composed of people who either like that sort of thing, or have managed to find a way to make that sort of thing OK in their mind, and if you are one of those, I hope you realize that my inability to make that sort of thing OK in my mind is not something I am doing to either you or Louis CK, but to assuage your concerns, you are swimming with the national current; the only thing you have to worry about probably is the occasional moment of implicit criticism that attends knowing that there are people who just don’t fuck with Louis CK anymore.

Not as much as been lost here, I suppose, as was lost with Bill Cosby. No massive legacy of cultural advancement for people to understandably want to try to salvage.

But something has been lost, and we might wonder what.

That’s how Louis CK lost his movie and his reputation, is a way I suppose you could put it.

Or that’s how I lost Louis CK, is a way I suppose you could put it.

And then I thought to myself: well, at least I still have Dave Chappelle.

Maybe you've noticed that it's getting harder to truly know what's going on these days. Legacy media—controlled by corrupt billionaires and addicted to the false equivalency of balance rather than dedicated to the principle of truth—has failed us. I am recommending that if you have money to do so, you subscribe to independent journalists and writers instead. This week I'm suggesting Pro Publica again. They do the important work of real journalism without being beholden to billionaire interests.

(If you also want to support The Reframe, there are buttons to do so all over the place and whatnot.)

I’m talking about comedy to illustrate how a national current carries everything along.

We can see it in other places as well, in the ways that we frame the exposure of an abusers’ abuses not as something being done to or taken from their victims by the abuser, but as something that is being done to the abuser, or something that is being taken from us by those exposing it; the way we rush to exonerate the abuser or try to provide some sort of alleviating context; the way we rush to find excuses to dismiss what we know; the way we look for reasons to not have to have a complicated relationship with something that had previously been uncomplicated.

It seems to me that another price I have to pay for noticing the national current of abuse now is accepting that I didn’t notice it then, which means I have to contend on some level not just with who Bill Cosby is, or who Louis CK is, but with who I am, who I have been, the assumptions I have made.

It means that I have to contend not only with the idea that I have been wrong, but the likelihood that I am still wrong about a great many things.

Having a complicated relationship with something or somebody that had once been uncomplicated means having a more complicated relationship with myself.

That’s the price we’re trying to avoid, I think.

We’d rather not pay the price of admitting the ways we’ve been swimming with the current, and we’d rather not have to stop doing so.

Bill Cosby sure did seem confused, didn’t he, when the shit went down? To me it sure seemed like he lived in a world where drugging women for sex was something that was such a common perk for famous or wealthy people to engage in if they wanted to, that you could write about it in a book and talk about it in a cable TV interview for yucks, and Larry King would just join in a call-and-response with you about it. Cosby didn’t seem like an abusive anomaly in an otherwise benign world who finally got busted. As good as it is that he was exposed and charged and convicted, it really seems that the anomaly of Bill Cosby was that he was one of the few dozen exposed, one of the few dozen who actually paid a price, and everyone else really resented the fact that they had to hold so very still, while so many people began swimming against their abusive current that the current itself was threatening to change direction.

And I can’t help but remember that the dominant phrase, as perhaps a few dozen people got exposed and Cosby’s reputation crumbled was, you have to be so careful now.

You … who? Not women. Women have had to be careful all along, is what we were learning. I’d say the people who have to be careful now were people who hadn’t needed to be careful before.

It sure sounded like the Me Too revelations resulted in a whole lot of people holding very carefully still in the water.

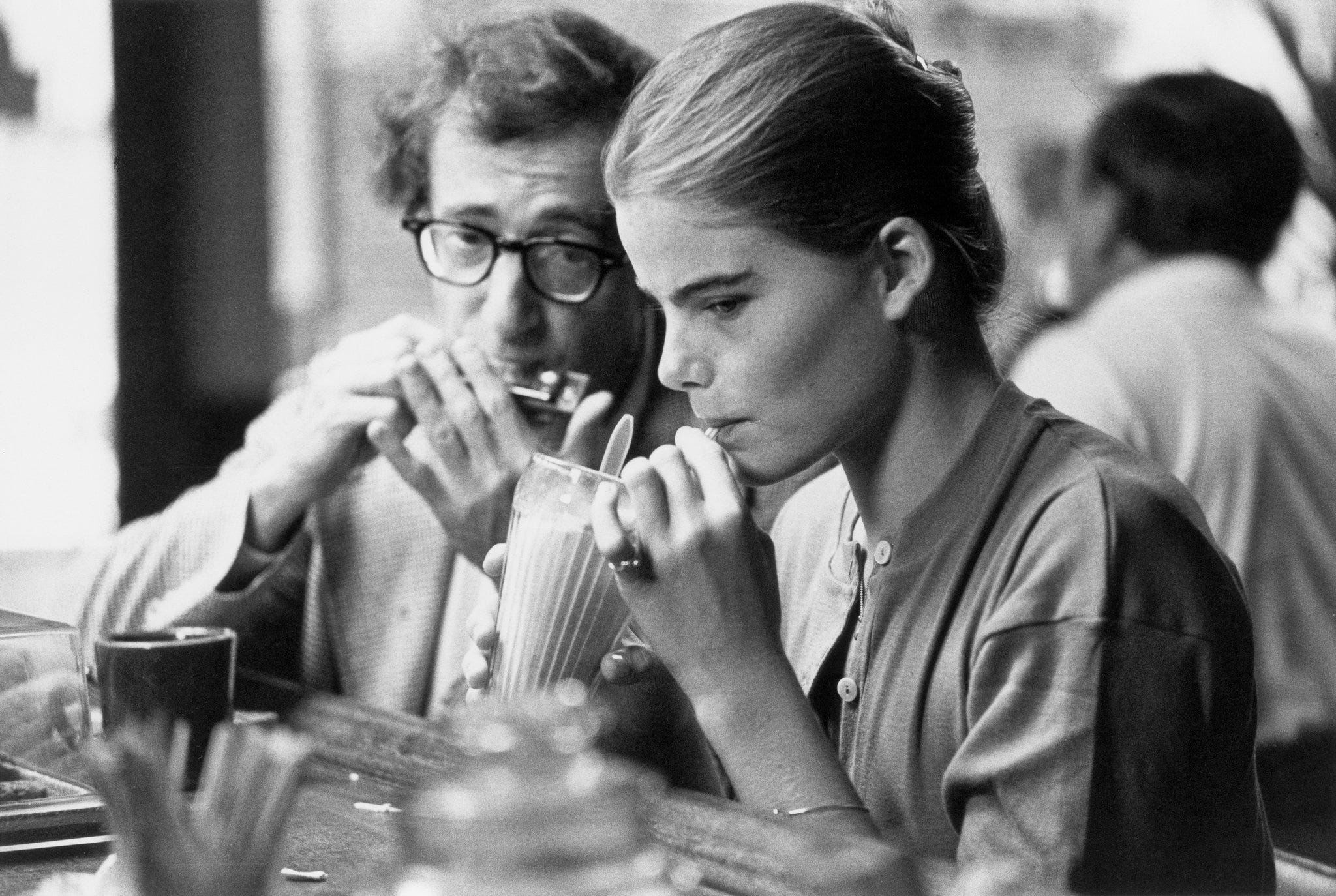

Woody Allen is still making movies, by the way. Speaking of comedy.

My favorite comedy of all time is Woody Allen’s Love & Death, one of the last of his 70s output of “early funny stuff.” It’s a spoof comedy that predates Airplane! but where the later movie spoofs corny disaster movies, Love & Death spoofs 19th century Russian Literature. I just think its goddamned hilarious. I still do.

But it isn’t an uncomplicated watch anymore. Its project really doesn’t seem to be anything beyond spoofing Russian literature and foolishness, but if you know about Woody Allen, you have to contend with his presence in the film, and the knowledge of what he has done.

I can do all that and still enjoy the movie. Others can’t.

Maybe you think I’m wrong for being able to do that.

Maybe you’re right to think I’m wrong.

But I can still watch it, probably because its project appears to mostly be silliness.

Manhattan, which Allen made some years later, is a different story for me.

Manhattan is an even better film, by consensus, than Love & Death. Since it came out it’s been regarded as an artistic triumph, not only for Allen but for cinema, and it is frequently pointed out, along with a handful of other pictures, as Allen’s high-water mark in terms of direction and cinematography and performance and scripting.

If I were to watch it now, I still daresay I’d see all those things, but it would simply be a different experience, because it also makes a positive romantic case for a 42-year old man being involved with a 17-year-old girl, and I know what I know.

It’s not to say that a movie taking on this subject matter is an inappropriate subject for art, or that our fictional characters must be moral. It’s to say that we have knowledge that breaks the fourth wall, and that knowledge matters.

Personally I find it sort of hard not to notice that grooming teens was exactly the sort of thing that Woody Allen wanted to do, and did do, even with his own children, and he used his art to help put that sort of thing into the current as a thing that isn’t only acceptable but erudite and sophisticated, and I don’t know if it made other people think that 40 year old men dating children is acceptable behavior, but it certainly gave me the impression that it must be something acceptable when I watched it in my early 20s, and I can’t help but notice that Woody Allen certainly wanted to live in a world where that was the impression people had, and a whole lot of comedians sure did grow up revering Woody Allen. I don’t remember how old Jerry Seinfeld was when he started dating a high school student, for example, but Wikipedia does. He was 38. Does Jerry Seinfeld revere Woody Allen? Forget it, Jake. It’s Manhattan.

Mariel Hemingway, who played the child that Woody Allen’s self-insert character “dated” (as the movie would have it), says Manhattan couldn’t come out today, which is perhaps true, but I don’t think that she means the masterful direction or performance or cinematography or scripting would be disallowed, or even that the subject matter of a 40-year-old man in what he calls “a relationship” with a high school kid would be disallowed, but simply the uncomplicated presentation of predatory sexual grooming as a normal and appropriate romance, in service of a creator who very much intended to pursue predatory sexual grooming and very much wanted that to be seen in the world as something normal and appropriate and romantic.

And I have to ask: would we want that to come out today? Why?

Wouldn’t we want the story told a different way, for better reasons?

Maybe you think that knowing what Woody Allen did and deciding that it changes my opinion on the greatness of Manhattan means that I am “throwing out” Manhattan.

I don’t know. Manhattan is still there. Anybody who wants to enjoy it for what it is absolutely still can, and they can follow it up with “Bill Cosby: Himself” if they want to. And Allen, unlike Bill Cosby, is still working, and actors who grew up revering him still line up to fulfill a lifetime dream of working with him, so you can check out his new shit if you want to. I don’t feel like I’m throwing out Manhattan or Woody Allen. It’s just that I am trying to swim against our national current, and it’s hard work, and if I watch Manhattan without also engaging in the vital work of directly contending with the clear intent behind it, I feel very much like I’m swimming with the current again. It feels like entering a world where women exist specifically and exclusively for the benefit of men, and what that means is romantic if the man involved says it is.

It seems to me that for women—particularly young women—watching Manhattan always needed to be a critical exercise. Only men could watch it and just float along on the surface. For women, I don’t think it can ever feel like swimming with the current; it can only feel like being carried along with it, or held underneath.

I think the question isn’t a question of what is permitted or what can be gotten away with, but what do we want to see permitted or gotten away with?

And why?

Would we rather know or not know, when our ignorance will cost somebody a lot, and our awareness will only cost us uncomplicated enjoyment?

Are we just trying to avoid the effort of swimming upstream, in places where we are permitted to just be carried along?

Is our reaction to new revelations that expose for us once again a national current that punishes victims and forgives powerful abusers simply finding an excuse—any excuse—to remove ourselves from any involvement?

And I could be talking about many other people besides Bill Cosby, or Woody Allen.

Turns out I could be talking about my favorite TV show, which is LOST.

The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work with a paid subscription. They pay what they want—more than the nothing they have to pay. It really helps.

If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any future books.

LOST is a mid-to-late-aughts mystery-drama television show that I’ve been spending most of the run of this newsletter subjecting to my obsessive review and speculation, hopefully to the amusement and enjoyment of many.

The reason I do this with LOST is that its narrative mode is one that will allow you to observe what the story actually is even while the characters are telling you something quite different, which means that in order to understand it you have to observe what actually happens, which can help you see whether a character’s assumptions about what they think is true is right or wrong, misguided or knowledgeable, and whether their intent is malicious or benign or good. And, where things don’t match up, you can use what you’ve observed to establish useful beliefs to create informed conclusions.

Which now that I think about it is sort of what I try to do when the topic isn’t TV, as well—like in this essay, for example.

The legacy of LOST had a pretty rough week recently.

That’s one way to put it, anyway.

Another way to put it is that we recently learned, via an excerpt from Maureen Ryan’s new book “Burn It Down,” that LOST’s legacy involves its famous and acclaimed showrunners giving a lot of creative people who happen to be women and/or people of color a pretty rough decade by fostering a culture of chronic harassment, bullying, and many instances of outright blatant racism. It was a culture where it was very important for people to be able to get away with saying pretty much anything, for a very specific definition of “people.”

If you read it, and you should. you’ll likely find it very upsetting. It’s far more upsetting than I was expecting when I started, that’s for sure.

So something, once again, has been lost—but what?

For one thing, the opportunities that should have come with being on the writing staff or being a featured actor on a mega-smash TV show have been lost for a lot of writers from minority communities—that, and peace of mind, and a non-toxic working environment, and probably a decent amount of money. A lot of interesting storylines were lost, that might have been told, about minority characters, told by people writing from the perspective of those characters.

These seem like the most important thing lost.

Also lost: some degree of reputation for lionized LOST showrunners Damon Lindeloff and Carleton Cuse. How much remains to be seen, but at least some with at least some of their audience. I suppose we could say that Ryan’s book did that to them, if we wanted to swim with the current. I’d argue that they did it to themselves, years ago, and it’s only now catching up to them.

And, at the very least important part of the spectrum, my ability to watch this complicated show in an uncomplicated way has been lost, as has my implicit trust in the intentions of the people at the helm. A big part of my project has been an assumption that, because I can perceive such cohesion to the story by applying an observation vs. belief dialectic, that the writers and showrunners were in far greater control of the narrative than they usually get credit for.

I still believe that. I just now have to realize the ways I was swimming downstream, and offering exonerations for narratives, and accepting the places where those showrunners were claiming events were out of their control.

Walt was written out because actor Malcom David Kelley grew too fast to be explained by the timeline. That was the story we were told, and if you go back and read my summaries, you’ll see that I accepted that explanation uncritically. Somewhere I might have mentioned my longstanding belief that the writers missed a really easy layup; a way to tease the time-travel element (which I think it’s clear they were already planning), but I didn’t find it if I did, and it doesn’t really matter, because I now know that—whether consciously or unconsciously—they simply didn’t find the stories involving minority characters compelling enough to be worth the time to fully tell, when they could focus on how Jack got his tattoos instead. I also know that when their failures of imagination were pointed out to them, they behaved as if that revelation was something aggressive being done to them, and they used their power to deliver punishment and bullying, and they knew they could get away with it, because the national current always flows to facilitate empowered abuse.

I’d assumed that the intentions of the creators of my favorite TV show were uncomplicated. And I was wrong. It turns out that in some ways, I was another John Locke, putting my faith in the wrong places in search of meaning, even while remaining certain that there is meaning to be found.

And that sucks, but not as much as it would suck if I just ignored it. One of the main themes of LOST itself is that we must observe before we believe, or we fall into disaster.

What else has been lost? My ability to go on recapping LOST?

Maybe.

Honestly, maybe so. Maybe not, but maybe so.

I hope not, but I really don’t know. It so happens I haven’t watched the show since Ryan’s excerpt dropped—I’d already watched the finale in preparation for that installment—so I don’t know how it will feel to watch episodes with my new knowledge. One of the upcoming episodes deals with the death of my favorite character, Mister Eko (spoilers), and some of the most viscerally upsetting revelations in Ryan’s book deal with that moment in the show’s creation. Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, who played Eko, left the show because he missed his family, is what I’ve been told.

I believed it. Now I know things that make that story seem far too neat. I think that episode is going to hit a lot differently now.

My plan for now is to finish the second season, and then take a break. I’ll return to Season 3 in late summer, and we’ll see what I find there.

So maybe I’ll bring the series back with a new perspective and new perception, or maybe my new perspective will be that I can’t find a way to bring it back.

Either way, I intend not to lose sight of what is lost, and what LOST is. I intend to carry my own piece of the responsibility for what I’ve missed, and think about why I missed it, and what that might indicate about what else I’m missing.

It’s a harder way of enjoying art, among other things, but it’s the more honest and productive way to encounter it.

May we always be found swimming upstream.

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries, and the essay collection Very Fine People, which are available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He would have been a good woman, The Misfit said, if it had been somebody there to shoot him every minute of his life.

Comments ()