Change the Locks

A tale of two sisters; the narcissist's demand for reconciliation without reparation, and the lowest rung on justice's ladder

Note - like Boiling Water, this is a slightly updated pull from a 2017 essay, which was part of a series called "Bubbles" that was reproduced in my essay collection "Very Fine People." This part was excised to accommodate that book's flow.

I was reading Mary Ann Dimond's very good daily newsletter the other day, and she was contending (very well) with what I believe to be a well-meaning comment to an earlier post, which was about the sort of just societal system we might wish to see replace the unjust one we have, and about those who would delay it in favor of a more favorable moment.

The commenter said:

“it can't just be a system I like. It needs to be one that the bullies will live within. Because the alternative is just to kill all of them, which seems like a really bad idea to me.”

It's a common refrain, and I understand the urge. The idea is that, in our rush to create justice, we would bring some sort of injustice to the unjust. The idea is that if we can't make a society that bullies will agree to live in, then we are in effect harming the bullies. This is often expressed, as here, in terms of mass murder. Thus, any dream of a society that bullies would find unacceptable is converted into a de facto mass murder. There are millions of them, I hear. We have to live with them. Elsewhere the commenter asks "how do we overcome the bully's sense of grievance?"

Many find this a challenging problem. Some offer it as a challenge, which is itself a problem.

Sometimes I find stories are a good way of thinking about challenging problems.

Let me tell you a story.

Once there was a brother and sister named Thomas and Mary, who moved next door to one another, along with their spouses, Sally and Abe.

Late one night, a knock came at Abe and Mary’s door; it was Sally, beaten badly, arm broken, eye swollen shut. Thomas had done this to her, she said. It wasn’t the first time; beatings had been going on for years. But tonight, for the first time in years, Thomas had pushed it further, had hit and not stopped hitting, had done damage he couldn't cover. Tonight she feared for her life. She went to the one place she could think to go. She went to her friends. She went to her brother and sister.

That night, at the hospital, Abe and Mary talked, and discovered many things now cast in a new light: Sally’s famous clumsiness seemed less accidental now, her tendency to drink heavily in social situations seemed compensatory, and certain of Thomas’s running jokes about Sally’s shortcomings revealed themselves as cruel and controlling. Thomas’s habit of playing loud music at odd hours now seemed calculated to mask other sounds. Mary remembered troubling rumors she'd heard, and soon discounted, of Thomas's behavior with Mary and other partners when he was in college out of state. Both perceived that a new menace now tinted actions and words that had previously seemed harmless to them.

In time, the police arrived, and, just after them, came Thomas, who explained that Sally had just been having an episode. It happened sometimes. He never mentioned it because he didn’t want to embarrass her, but last night she'd gone too far. She’d gotten drunk and angry, he claimed. She’d started screaming at him (look, she’s screaming now). Then, out of the blue, on purpose, she threw herself down a flight of stairs.

Thomas was deeply disturbed by Abe and Mary's reaction to him. He was shocked, offended; they’d gotten him all wrong. She was doing this to get back at him for imagined offenses. And he was a good person—they knew him, so they knew he was a good person. How could they believe this of him? And, they had to admit … Sally was a a drinker, no? A bit of a lush? And ... by the way, how was this anybody else’s business? He was very calm and very logical.

The police asked Sally if she had been drinking last night. Sally admitted she had.

The police cleared their throats. They asked Abe and Mary, do you really want to give a statement?

Abe decided not to give a statement. After all, Thomas was his friend and brother. And, he reasoned, both sides have some part of every quarrel. And he knew Thomas, and knew all of his amazing qualities. It was impossible to think his friend—his brother—was an evil man.

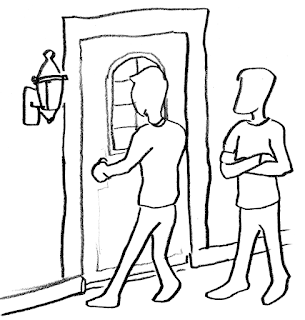

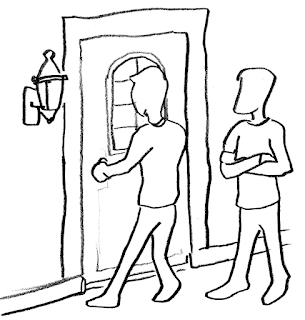

But Mary gave her report to the police, and stood with Sally as Sally gave hers, and when Abe left them both to bail out Thomas, she brought her sister into her own home and changed the locks. When Abe returned with Thomas, neither of them could get in anymore.

When Thomas demanded to be let in to see his own wife, Mary told him, I love you. But things aren’t the same anymore, now that I see what you’ve done.

When Abe demanded to be let in to his own home, Mary told him, I love you. But things aren’t the same anymore, now that I see what you’re willing to allow.

And Thomas berated his wife, growing ever angrier for alleged lies against his character, and shouted that her behavior now merited the treatment she had falsely claimed to have received. And Abe scolded his wife, for her harsh tone, her close-mindedness, her unwillingness to hear both sides. But Sally would not deny what she knew had happened. And Mary refused to open the door, no matter how hard Thomas pounded.

And both Thomas and Abe were angry and offended, and they went off to complain to each other about the uncompromising attitudes of their wives.

And Sally wept, because she was abused and vulnerable, and she mourned, because she had been beaten and disbelieved.

And Mary mourned, because Thomas was still her brother, and Abe was still her husband.

And she wept, because Sally was her sister, and her sister was abused.

Or don't subscribe. I'm not the boss of you. But if you do subscribe, my gosh the splendors that await you.

Let me ask you: who, after listening to that story, wants Sally to go back to Thomas?

Well, Thomas does, for a start. Thomas is an abusive person. What Thomas wants is what abusive people want, which is reconciliation without reparation. He wants continuation of the power that allowed the abuse, and the permission to continue that abuse without consequence. An abusive person wants your complicity.

And if he can’t have that, then he wants everybody to pretend. He’ll deflect. He’ll call attention to all the things he does that aren’t his abuse, and wonder why you won’t focus on those. He’ll insinuate that the existence of good deeds and good qualities make the bad qualities impossible. Evil people beat their wives. I have done these good things. Therefore I am not evil. Therefore I do not beat my wife.

And if everybody won’t pretend, he’ll want everyone confused. He’ll lie. He’ll tell you that what you both know happened didn’t happen. He’ll tell you that he didn’t say what you know he said. He’ll tell you you did say what you know you didn’t say. He’ll insist. He’ll make you start to wonder if you’re crazy. Convincing you the lies are true is not the point; making you wonder if you’re crazy is the point—because if he can establish that you are confused about one thing, then he can claim that you’re probably also confused about him, too.

And if you won’t get confused, he’ll want you to ignore. He’ll promote a theory that he’s no worse than his victim. He’ll point out all the ways his victim is at fault. He’ll make the case that any bad thing is equally as bad as any other. Because if his victim is as bad as he is, then he and his victim deserve each other—and what business is it of anybody’s anyway? The abuser wants your adoration, but he’ll accept your apathy.

And if you won’t ignore, than he’ll rage at how unfairly he’s being treated. He’ll insist he is a misunderstood victim in a situation that has sprung up all by itself. He’ll lash out. He’ll make it uncomfortable, and offer removal of the discomfort as incentive to comply. And if you comply, he’ll flatter you as a reward—until next time.

Most of all, an abusive person wants to be the priority. To the great philosophical question “what is the most important thing?” the abusive person answers: “I am the only thing.” The one thing an abuser cannot abide is something that interferes with his ongoing favorable self-regard. An abuser can never do wrong. He can only be wronged. An abuser always has to be both the hero and the victim of his own story. An abuser will always try to impose his reality upon reality.

It won’t be effective to debate an abuser who is engaged in this sort of narcissistic death spiral, or to engage in convincing them to stop. An abuser has to be opposed, and then defeated.

I hear some ask: But how? With more abuse? Sure, we owe something to Sally, but don't we don't we owe something to Thomas? Sure, Sally is part of our community, but isn't Thomas part of our community, too?

Who wants Abe to side with Thomas? Who wants Mary to open the door for him? Who wants Sally to return to him?

Nobody, I hope. But I know better.

Nor do I harbor any illusions that there are people who want Mary to open the door for her husband. I hear the arguments. What did Abe do, anyway? He’s just trying to give everybody a fair hearing. He just wants to offer benefit of the doubt. He just wants to hear both sides.

But here’s Sally. Her face a bruise. She’s come to you for help. She’s undeniably abused.

And here’s Abe, whose first instinct is to … try to get things back to normal, without addressing what is wrong.

I understand Abe. In my weaker moments I tend toward en-Abe-lement, myself. Who doesn’t want to see things go back to comfort and ease? Who doesn’t want everybody to get along? Who doesn’t want to restore right relations, to forgive and forget? I hear some ask: Isn’t forgiving good? Why are you against forgiveness, anyway? And isn’t reconciliation a good thing? Restoration of right relationship? Why would you be so divisive?

I hope we all see the problem, which is that the divide is real, and it is caused by abuse, and only the abuser can reconcile that divide, and only the abused party can forgive the abuse. Furthermore, there’s only one path for the abuser to reconcile, which is to recognize his abuse for what it is, and admit to it, and apologize—to the victim, not to someone else—and then, crucially, to accept the consequence of what he has done. Only then is it appropriate for others to begin to consider anything like reconciliation. Before that happens, there is no true reconciliation, only the false reconciliation of enablement, which makes future abuse not only likely, but also inevitable.

It isn’t anybody else’s place to speed the process. Cajoling a victim under threat of abuse to reconcile with their abuser, while still under threat of further abuse, is itself abuse. Reconciliation without reparation is the abuser’s desired end, and they mustn't be given it.

What the abuser demands is an apology from his victim, and they don't need the victim to be the one to deliver it. What Thomas is offering Abe and Mary is the opportunity to apologize for Sally by proxy, to forgive him for crimes he committed against somebody else, not because they are the ones made vulnerable by his abuse, but because their safety gives them the power, the ability, the leverage, to smooth it all over.

Abe accepts the offer. Mary changes the locks.

The difference doesn't matter much if your frame is order over justice.

The difference matters, a lot, when your frame is justice over order.

I should define these terms, which are often confused for one another. For these purposes, let's take order to mean "a system which, to the best of its ability, maintains itself with consistency through any attempted disruption, whatever its flaws" And let's take justice to mean "the extent to which a system recognizes and ensures, to the best of its ability, the essential dignity, equal standing under the law, and basic physical and spiritual needs, of all human beings."

What I've noticed is that when justice and order come into conflict, most human beings tend to prefer order. When an interested and unabused third party reconciles with an abuser while that abuser's victim still lives under threat of abuse, it betrays the victim, leaves her stranded, friendless, vulnerable. It’s inappropriate. It’s complicity. And it is very, very, very tempting—tempting, because it does restore order, and only the abused party has to pay ... at least at first.

It’s worth noting that order isn’t a bad thing, taken by itself. But order, like so many other good things, becomes corrupt when it is elevated inappropriately above its station. And, as any corrupt order will eventually collapse, justice must be considered a higher priority.

Sometimes, restoring order is inappropriate. Sometimes, maintaining order is abusive. Sometimes, your sister is bleeding and frightened for her life. Sometimes, the only appropriate thing is to change the locks—whatever that might look like.

What might that look like, especially in a time like now, when abusive bullies have full run of the national house?

Maybe changing the locks looks like this: Refusing complicity. Not letting people infer through your silence that you think their beliefs are good and just and true, rather than unjust and harmful.

Maybe changing the locks looks like this: Refusing distraction. Not allowing the existence of a person’s good qualities to distract from the fact that a person’s beliefs are unjust and will make abuse not only likely, but also inevitable.

Maybe it looks like this: Refusing to be confused. Insisting on the truth. Not accepting a deflecting flurry of lies. Not accepting a false reality.

Maybe it looks like this: Refusing to ignore. Not giving in to the temptation of comfortable apathy.

Maybe it looks like this: Refusing debate with someone whose methods and purposes are abusive, simply on the grounds that they are being abusive and you refuse to be abused.

Maybe it looks like this: Reporting a crime being committed by a powerful person against a powerless person, and accepting the danger that such a report brings to the one who reports it.

Maybe it looks like this: Putting your body between somebody who might be harmed and the person who intends to harm them—without violence, if possible, and if you possess sufficient physical bravery.

Maybe it looks like this: Listening to somebody talk about their lived experience of oppression without deciding the conversation needs your perspective. Understanding that some conversations only need your ears, not your voice.

Maybe it looks like this: refusing to scold a person who happens to live under daily persistent threat from powerful people for the tone or methods they use to cope and survive. Or maybe it’s supporting people whose family faces separation, whose marriage faces nullification, whose child faces bigotry and hatred, who represents a presumed danger to armed authorities oriented upon violence—and supporting them even if their responses to these outrages and threats are not as polite as you might prefer. Maybe it looks like this: allowing yourself to absorb some of the criticism, and even some of the daily persistent threat, and maybe even some of the abuse, by associating with people who have been made vulnerable by an unjust society, and who therefore are mistrusted and feared by that society.

Maybe it's recognizing the places where you are society's accepted and preferred default, and the ways that other people are not. Maybe it looks like a sincere apology to somebody you hadn't realized you'd wronged without trying to offer your justifications. Maybe it's realizing that in any story, the person who persists and overcomes injustice is the hero, and that means that the real hero of our country's story is somebody other than yourself. Maybe it looks like working within the system—taking to the streets in protest, calling your representative every day, organizing and canvassing and voting. Maybe it looks like direct action outside of those channels.

Maybe it means letting things get uncomfortable and stay that way. Maybe it's saying to somebody close I love you. But things aren’t the same anymore, now that I see what you’ve done. Maybe it's saying to somebody close I love you. But things aren’t the same anymore, now that I see what you’re willing to allow.

Maybe it looks like not trusting somebody who has proved themselves unworthy of trust. Maybe it looks like lying to them about your intentions so that you can thwart theirs. Maybe it looks like sabotaging their efforts. Maybe it looks like locking them out of whatever part of the national house you still control, without asking their permission.

Here’s what it always, always, always looks like: Insisting on keeping the frame of the discussion at all times fixed upon the issue of justice. Insisting that we are all one human family. Insisting that life is not earned. Insisting that human value is not determined by human profitability. Insisting that all people—all people—are unique and irreplaceable works of art carrying unsurpassable worth, who possess inherent dignity, and who deserve equal consideration under the law and access to basic human need, simply because they exist.

Insisting that all other good things are only good insofar as they are not elevated above this essential truth, that any good thing that is elevated above this essential truth ceases to become good, insisting that any order that would preserve injustice must be dismantled and rebuilt.

Reframe upon justice that recognizes all mediums of human art. Insist upon this new frame. Reject all others.

Doing so will offend those of us who have different priorities.

Good.

Another quick interruption to scroll quickly past before you continue the essay.

The Reframe is me, A.R. Moxon, an independent writer. Some readers voluntarily support my work and pay whatever they want. Why would you pay for something that is free? Click the button; answers await you.

Good? Offense is good?

Let’s consider tolerance and offensiveness.

People who prioritize justice over order frequently talk to people who prioritize order over justice about tolerance; they frequently speak about how a lack of tolerance can be offensive—which is true. From that one might get the idea that the whole point is not being offensive, or that tolerance is the same thing as inoffensiveness. This misses the point, and in 2025 I have to believe we are all familiar with the Paradox of Tolerance by now, so missing this particular point feels like a conscious choice. Inoffensiveness is not the point. The point is justice. Our frame is justice.

We must focus, not on inoffensiveness, but on establishing a system that consistently recognizes the basic inherent human dignity of all people without exception, and prioritizes the full inclusion within public life and fulfillment of basic human need for all people as non-negotiable moral imperatives, because we are all one human family, and life is not something you have to earn.

That’s tolerance. It’s the base line. We tolerate the KKK, or Republicans, or the Proud Boys, or other hate groups, insofar as that, though we find their bigoted beliefs and abusive actions disgusting, and though we will pursue and deliver consequences (social or legal as is appropriate to each offense) for their crimes against humanity and justice and society and human dignity, we do not stop recognizing their essential dignity, equal standing under the law, and basic physical and spiritual needs, because even though we can see they have reviled their own humanity through their dismissal of the humanity of all others, they are still human beings. If they get cancer, we think they should be treated. If their child is hungry, we think she should be fed. If they lose their home, we think they should be housed. Tolerance doesn't mean we fail to expel an abusive person from polite society for their abuses against people in society. It means only that we have liberated ourselves from the cycles of abuse the abuser will create if he is allowed in. It means we recognize that a society's politeness isn't worth anything if the politeness is used as a shield for abuse.

Tolerance is the lowest rung on justice’s ladder. If you can't manage it, then you aren't even on the ladder. If you can't extend society to everyone, then you aren't participating in society yet, and cannot make any just demand upon any good thing that society provides. Tolerance is such a short curb, and so many, unwilling to lift their foot an inch, will loudly complain when they trip over it and fall, will present their skinned knee as evidence of a system arrayed against them, failing to disclose the ways they would expel others, failing to disclose the ways that they have arrayed themselves against any system worth preserving.

Finally, tolerance is something meant for unjust humans. Tolerance is no virtue when applied to unjust ideas or unjust acts. Against such things there must be no tolerance, if there would be justice.

Offense is a bit different than intolerance. Offense is thick on the ground; everyone can get a handful. Offense is what happens when one person refuses to accept the values of another as true or valid. But our frame is not inoffensiveness; our frame is justice. And offensiveness is not injustice—because what if somebody’s most deeply held values are provable untrue, and indecently unjust? It isn’t hard to imagine such a proposition in this society of ours, which is captured by a spirit that craves genocide and slavery.

Intolerance of people is both offensive and unjust.

Intolerance of values is offensive to those who hold the un-tolerated values, but whether or not that offensiveness is a product of injustice depends on what those values are.

The difference matters a lot. We have the right to not be treated unjustly. We do not have the right to not be offended, particularly if we ourselves resent being asked to acknowledge that other people exist. We don’t have the right to have our unacceptably unjust beliefs accepted.

Nor, it must be said, do those who prefer justice to order have the right to not be offended, nor should we seek to not be offended by offenses against justice. Those who prefer justice will offend those who prefer an unjust order. Those who prefer to maintain an unjust order will offend people with a preference for justice.

Be offended by injustice, because it is the natural and correct response to injustice. But don't dwell in your offense, or frame the conversation there, because causing offense is not the offensive thing, and offense is something we should be causing, too. Turn the conversation to matters of justice and injustice instead, and get ready for the demands of justice to cause serious offense. When one is opposing injustice, the offense of unjust people is inevitable. Offense should be expected. Offense should almost be desired.

Desired? Wait. Surely I don’t mean that. Desiring offensiveness?

Isn’t it better to be polite than impolite, civil rather than uncivil?

In many cases, yes.

Politeness isn’t bad. Politeness is good. Comity is good. Civility is good. It’s just they aren’t the most important thing—justice is. Moreover, they are the outcomes of justice, not the causes. If you try to create justice through civility and comity and politeness with justice, you create a counterfeit of justice. When elevated to a status more important than justice, these outcomes, like any other good thing improperly promoted, become corrupted and toxic.

Choosing politeness is often a luxury the powerful afford themselves. When I have total control over a situation, politeness is easy. It can be my way of signaling moral authority, even as I profit off of grotesque abuse. More than that—when I am an abusive person, civility is often the way I make my abuse polite. It’s how I bring order to injustice. (We already know this, by the way. Think of the stories we tell ourselves. Our most chilling villains are frequently urbane, cultured, and polite. It’s an indicator of how chillingly powerful they are, how dangerous it is that they should be able to become likeable.) And the powerful will frequently demand civility of the powerless as prerequisite to any consideration of their demands.

An excellent indication that you are successfully changing the frame to justice is this: People will start wanting to talk about politeness, who were strangely never worried about it before. The tone you’re using in the conversation will suddenly become the most important thing, much more important than the actual topic of conversation. Civility will suddenly begin to matter among those who in the recent past made successful use of shocking incivility.

Always remember our frame. We are framed on justice. Intolerance of injustice is deeply offensive to unjust people. Intolerance of injustice is also absolutely necessary, if what one seeks is justice. So, if you can be polite, be polite—by all means, be polite. Politeness opens the door to the possibility of persuasion, civility ingratiates in ways that might change a mind. But never forget that politeness and civility are choices that can be made from a position of power, and can therefore be used as a weapon of the powerful against those without. If you are able to choose civility when you are opposing injustice and abuse, I certainly recommend that you do so. But do not dare scold someone else for their incivility, as a way of closing them from their demands for justice. Do not dare pretend to make yourself the hero of their story, when they are of necessity being many times braver than you just by existing in an environment that is hostile to them.

There are millions of them. We have to learn to live with them. Actually, we already live with them. There are millions of us, and they have yet to learn to live with us. We have to recognize that when it comes to living with millions of others, they are the ones who refuse to even try. We have to recognize that when it comes to living with millions of others, they are the ones who actively oppose the idea.

How do we overcome a bully's sense of grievance? It's not ours to overcome; it's theirs. Their frame is grievance. Our frame is justice. We will build a just society that will tolerate them to the extent that they are willing to tolerate others. If they can't step on the lowest rung of justice's ladder, then they have chosen to not participate in a just society, and we must allow them the choice, and leave them to the consequences of that. We must change the locks. Bullies have the run of the house today because those with the power to lock them out spent a century of decades enabling them instead, in the name of protecting a civil society that is now burning in an arsonist's fire.

We might hope still to build a new house. If we do, it will need new locks.

Some will still think I’m saying civility is bad. I am not. Civility is good. But our fight is one of priority between competing good things. And civility is not more important than justice. In a just society, civility would obviously be preferable to incivility. In fact, civility would be a natural result of a society based on justice. It would not need to be called for; it would simply be. But impoliteness is not injustice. And justice will offend the unjust. Justice, it must be said, is, frequently necessarily impolite in an unjust society.

What an abuser wants is reconciliation without reparation.

So work on reparation. And change the locks.

The Reframe is totally free, supported voluntarily by its readership.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. If you'd like to be a patron of my work, there's a Founding Member level that comes with a free signed copy of one of my books and thanks by name in the acknowledgement section of any books I publish.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries and the essay collection Very Fine People, which are available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. Don't cross him, don't boss him, he's wild in his sorrow, he's ridin' an' hidin' his pain.

Comments ()